A bolt action, internal magazine rifle designed by Norwegians Ole Herman Johannes Krag and Erik Jørgensen, the “United States Magazine Rifle, Caliber .30” would be produced by Springfield Armory for the US military beginning with the Model of 1892. The rapid arms development of the late 19th Century saw tremendous improvements to the standard issue service rifle in a very short period of time, and competing designs would run the gambit in style of operation. The Marine Corps, falling under the Navy’s Bureau of Ordnance, would be equipped with James Paris Lee’s straight pull M1895 Winchester Lee-Navy Rifle for most of the 1890s, not adopting the “Krag” until the implementation of the M1898 variant. Combat against Mauser-equipped Spanish forces in the end of the decade would show weaknesses in both the .236 Lee Navy and .30-40 Krag cartridges, and the US War Department would take notice, beginning the search for a new design with the beginning of the 20th Century.

M1898 Krag documented to the US Marines (Tim Plowman collection).

In 1899, the First Marine Regiment would see limited combat in the Philippines against insurgent forces known as “Insurrectos” in the town of Noveleta. These Marines were armed with Krag rifles according to historian and Marine Colonel Brooke Nihart, and it is likely that these early actions would have been the first where Marines put their M1898s through trial by fire. The Marines in the Philippines did comment they preferred the stopping power of the Krag to that of the Lee Navy, as the Lee Navy tended to over-penetrate targets at close range, an issue immediately recognized as a potential problem in a Bureau of Ordnance report from 1895. Not long after the combat in Noveleta, part of the 1st Marine Regiment would be ordered to China to aid Captain Johnathon Twiggs Meyers and his embattled Marines at the American embassy in Peking who were under siege from the Chinese “Boxers” in what would be known as the Boxer Rebellion. Upon arrival in China the elements of the First Marine Regiment would combine with a newly arrived Marine detachment from Cavite to form a hasty battalion under the command of Major Littleton Waller. The Cavite detachment would be armed with older Springfield Armory M1884 Trapdoor rifles, complicating the logistical situation. Fierce combat would meet Waller’s battalion at Tientsin, where one of his handpicked officers and friend Lieutenant Smedley Butler would be wounded as he helped a wounded man to safety. This action would see Smedley Butler given a brevet promotion to Captain for his heroism. Following further action in China, Waller and the rest of the First Marine Regiment men would return to the Philippines, where significant combat awaited in the following years.

“In the days of dopey dreams — happy, peaceful Philippines, When the bolomen were busy all night long. When ladrones would steal and lie, and Americanos die, Then you heard the soldiers sing this evening song: Damn, damn, damn the insurrectos! Cross-eyed kakiac ladrones! Underneath the starry flag, civilize ’em with a Krag, and return us to our own beloved homes.”

-“The Solder’s Song,” a popular ballad sung amongst the American troops who fought in the Philippines.

The Boxer Rebellion saw an amalgam of Marines engaged, and they carried an eclectic mix of primary weapons. The M1884 Trapdoor, M1895 Lee Navy, and M1898 Krag were all present in the fray, with the later two the most common (Tim Plowman collection).

By far the most intense combat environment Krag armed Marines would see would take place during Major Littleton Waller’s infamous march across Samar Island in the Philippines in late 1901. Samar Island had always proven difficult to US forces, but it would become a nationally recognized place with the Balangiga Massacre, when Insurrectos would ambush the soldiers of C Company, 9th Infantry Regiment while they were eating breakfast in their mess hall. In total, forty-four soldiers would either be killed or die of their wounds, twenty-two would be wounded, and just four would escape unharmed. Public outrage and comparisons to General Custer’s defeat at Little Bighorn led to President Theodore Roosevelt’s orders for the island to be pacified. to this end, army general Jacob H. Smith would task Major Waller and his battalion of 315 Marines to march across the island, destroying any and all opposition. General Smith would order no prisoners to be taken, villages to be burned, and any male older than ten be executed as a criminal. The Insurrecto forces under General Vicente Lukbán swore to fight to the death, making the situation on Samar a powder keg from the start of retaliatory operations. Marines would instantly begin pushing out patrols in search of the enemy, and in the various engagements that would follow weapons and gear from the ambushed 9th Infantry soldiers would be recovered from the dead Insurrectos and their encampments. The tenacity of the Marines and string of defeats the Insurrectos would suffer at their hands led to their retreat into the dense jungle, where prepared positions awaited on the cliffs of the Sohoton river. Major Waller and his Marines would begin drawing up plans to pursue them immediately.

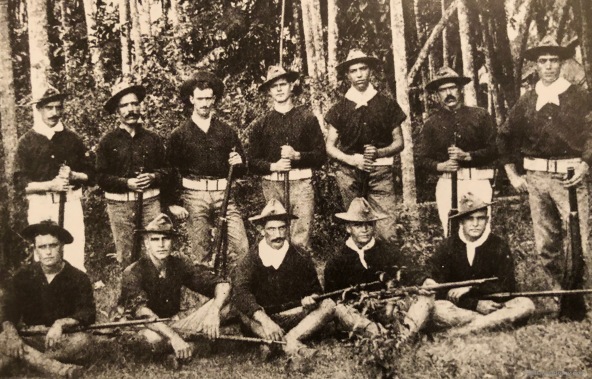

Marines on patrol in the Philippines. During the bloody Philippine insurrection, the Marine Corps would be famously (and notoriously) be engaged in the fighting on the island of Samar (photo: USMC).

Major Waller’s Marines would launch their assault on General Lukbán’s position with a three pronged assault, two columns moving by shore and the other by way of the river. The shore columns would reach the Insurrecto position first, and set up a devastating support by fire position, where Gunnery Sergeant John H. Quick’s Colt-Browning M1895 machine gun swept the Insurrectos rendering them unable to mount an adequate defense. This allowed the shore columns to sling their Krag rifles and draw their Colt revolvers, and scale the 200 foot cliffs for their assault. The Insurrectos would lose thirty men killed, and while some would escape, General Lukbán and his lieutenants were captured, rendering the Insurrectos leaderless and effectively dispersed. The slaughter at Balangiga was avenged, but the Marines most infamous events on Samar remained yet to come.

While Marine the Marines would defeat the Insurrectos whenever they met them, exacting American revenge for the Balangiga Massacre, they would find a far more difficult enemy in the jungle itself. The ill-fated march across Samar would see ten Marines die due to the extreme, flooded conditions (photo: USMC).

The march across Samar would be born out of General Smith’s desire to reconnoiter a path for telegraph line to be strung across the island, connecting the east and west coasts. Major Waller was highly advised against it, but recorded the following, “remembering the general’s several talks on the subject and his evident desire to know the terrain and run wires across, coupled with my own desire for some further knowledge of the people and the nature of this heretofore impenetrable country, I decided to make the trial with 50 men and the necessary carriers.” Waller would split his men into two groups, and within several days they all would be in poor shape. The sharp, rugged mountains destroyed boots, and the constantly wet conditions saw the Marines begin to fall ill. A message sent by Filipino courier from Waller to Captain David Porter, one of the heroes of the Sohoton victory, instructing him to rest his men in a patch of land that had sweet potatoes and fruits would never be received, as the courier later reported he was too afraid of Insurrectos to proceed. The lack of this message, with instructions on how to reach he indigenous food would prove disastrous. A week later, Waller’s men would arrive at their destination, which he described in doing detail, “the men, realizing that all was over and that they were safe and once more near home, gave up. Some quietly wept; others laughed hysterically… Most of them had no shoes. Cut, torn, bruised and dilapidated, they had marched without murmur for twenty-nine days.”

Captain Porter’s men, who had taken an interior route through even more dense vegetation and mountains, would not be able to finish their march. Out of food and in with half the men in a terrible state, Captain Porter would take the most healthy of the Marines from his party and head back to their starting point in Lanang in effort to organize a relief party. The Marines too weakened or sick to travel would be left under the command of Lieutenant A.S. Williams. At the same time, Major Waller, despite him and his men being weakened from their journey, set out searching for Captain Porter’s group after just twenty-four hours of rest. Their efforts would be unsuccessful, and after nine days Major Waller would be hospitalized with fever. Captain Porter would reach Lanang, and instantly begin to coordinate with the army post in organizing a rescue mission. The situation was dire for Lieutenant Williams and his men, and necessity dictated they depart their hasty outpost and begin the trek to Lanang. Ten of Williams’ men would die on the egress, some being left to die on their own as the situation reached the height of desperation. The Filipino porters attached to Williams had began stealing and hiding food amongst themselves, and eventually attacked Williams himself. Williams and the survivors of his group would be rescued a day away from Lanang, and Waller ordered eleven of the Filipino porters summarily shot as criminals. The army brass would eventually charge him for these executions, but the court martial would dramatically turn in another direction, with the charges against Waller dismissed and General Smith forced into retirement. The executions, even if arguably justified, brought with them much negative press in the United States, and Waller with the moniker “the Butcher of Samar.” While some minor skirmishes would follow in the next few years of the Philippine War for the Marines stationed there, they were minor in nature. The combat service of the M1898 Krag rifle in the hands of US Marines had ended.

The Marine Corps rifle team in Camp Perry, Ohio for the National Matches, late 1900’s (photo: NARA).

The Krag was also the rifle that begat the lore of the Marine shooting team. Initially, the Marine team was badly beaten by their peers on the US Army team, leading to rigorous marksmanship training in order to become competitive at the National Match level. As the Marines behind the accurate Krag rifles started to properly employ them in a bullseye setting, they would see a significant improvement from the National Matches at Camp Perry to international matches abroad. As good of a rifle as the Krag was, its rimmed cartridge would quickly be rendered obsolete by the development of the .30 Caliber, Model of 1906 round, known colloquially as the .30-06. The Krag’s tenure with the US Marines would last for over in a decade, giving way to Springfield’s M1903 rifle after its original .30-03 design was updated to the superior .30-06. The Krag would be adopted by the Corps not long after the implementation of the 30-06 rounded fully implemented.

With a surging popularity in competition shooting, in no small part due to the increase in accuracy in service rifles, small teams popped up from all corners of the armed forces. This ship’s rifle team, comprised of Marines and sailors, pose with their match trophy (photo: collection of Chief Quartermaster John Harold, USN).

Future Marine Corps Commandant Thomas Holcomb and his rifle team in China, 1910, the last year of mainline USMC service for the Krag (Marine Corps University).

The USMC preferred the M1901 rear sight, which had a peep sight that is similar to the sights of the M1884 Trapdoor and M1903 Springfield. The prevalence in M1901 rear sights on Marine Krags in photographs, despite the wide variety of types of rear sights employed on Krag rifles throughout their service history shows the Marine preference for the peep sight system (Tim Plowman collection).

Identifying USMC Krags is practically relegated to identifying one through documentation. This obviously makes identification very difficult, as the number of of all USMC documented Krags combined is just over 1000. Most of these rifles were sent from the Philippines to California after the end of hostilities in the Philippines, the remainder belonging to the Marine Corps rifle team or other various surveys. Of the two USMC Krags documented through the National Archives, both were from the Philippine shipment. The odds of these rifles having seen combat are significant, and perhaps the best of any Marine rifles to be found today. Besides National Archives documentation, the Marines did display a preference for the M1901 rear sight, making any M1898 Krag rifle with a M1901 sight a good placeholder for the Marine weapons enthusiast.

M1898 Krag-Jorgensen Rifles #231425 and 257294. These rifles are two of a thousand transferred from Marines in the Philippines to the Marine ordnance officer at Benecia Arsenal in California after the end of the Philippine insurrection. Former Marine and exceptional author Alec Tulkoff discovered the documents behind the story of this rifle and the others like it, and tells their tale in his book “Equipping the Corps, Volume I: Webgear, Weapons and Headgear. As of now, these are the only two documented, USMC provenance M1898 Rifles to have been identified (documents: Alec Tulkof, rifles: Tyler Anderson & Tim Plowman collections).

Springfield Armory M1898 Krag-Jørgensen Rifle #231425 (Tim Plowman collection).

Much of the Krag’s service history with the USMC would take place at sea with Marine detachments on cruisers and battleships (photos: USMC & NARA).

Marines during duty in China. Far East Marines were to be the first armed with the M1898 Krag, and their occupation duties continued long after the Boxer Rebellion, and would until the beginning of World War Two (photos: www.chinamarine.org).

Krag armed US Marines in China, 1908 (David M. Doody/Janus Images).

Left: Though ordered decades after the Krag left front line service, Marine preference for the M1901 peep sight reinforced by this order from Rock Island Arsenal. Considering where this document was found in the National Archives, it is highly likely these parts were for Krag rifles that were used to equip Nicaraguan and Haitian allies (document: NARA). Right: Weapons permit document from Nicaragua. Many Nicaraguan allies would be armed with Krags and other US small arms during the American occupation there (document: NARA).