The M1903 Springfield rifle would usher in an era of ground breaking marksmanship and ballistic capability. Duly, sniper rifle variants would soon follow. Originally chambered in .30-03, the subsequent .30-06 round provided the M1903 with the ability to accurately engage targets to a standard unprecedented in a service rifle. The army would begin work on the addition of a scope to the M1903 nearly as soon as it was adopted, resulting in the implementation of the M1908 Warner & Swasey Musket Sight. The Warner & Swasey was not without issues, as the very short eye relief and slight offset of the design made shooters wary of recoil, creating issues with accuracy. Internally, Warner & Swasey scopes used a system of prisms, which could find themselves knocked out of alignment. Aside from giving shooters an occasional black eye, the rubber eye piece was problematic internally as well, trapping moisture inside and causing the eyepiece to get foggy. The Marines would adopt the M1903 rifle in 1909, and with their initial compliment of rifles including ten mounted with Warner & Swasey scopes. The Marines specifically requested the Warner & Swaseys as marksmanship training aides, believing the magnification would be useful in further educating marksmen in their craft. While documentation is limited as to the reason why, the Marines did not pursue acquiring Warner & Swasey rifles for operational use.

M1908 Warner & Swasey equipped M1903 sniper rifle.

Marine Corps interest in a scoped M1903 would begin in earnest in the years leading up to American involvement in World War One, with the advent of the Winchester A5 scope. The army would take the lead in testing the new Winchester scope, and on February 12th, 1914 twelve A5 scoped rifles were sent to the Ordnance Department for evaluation. These rifles would have the rear block mounted on the flat portion of the M1903’s rear sight base, in lieu of the rear sight. The advantages to this were dual in nature: the flat surface allowed for a much easier installation process, and by avoiding drilling the receiver itself the most valuable part of the rifle was left untouched. The downside to this style of mounting was the relatively close six inch spacing between the front and rear sight blocks, which made the free-floating rear half of the scope prone to damage. The six inch spacing also meant that every windage or elevation adjustment made would be in six-tenths of an inch increments per one hundred yards. The mathematics of this would prove difficult, especially for snipers that would be expected to estimate distance and wind under fire. Over the course of several years, studies would be conducted and the Ordnance Department would decide against the design. Winchester would inquire as to why the Ordnance Department had come to a negative conclusion, and it was clearly communicated that the rear block would have to be reevaluated in regards to where it was mounted. Moving the rear block back to the top of the receiver would allow for seven and two-tenths inch spacing between the blocks, equating to half inch adjustments per every hundred yards. The larger gap between the two scope mountings would also improve the fragility problem, and make for a more durable scope setting. By the spring of 1917 Winchester was well aware that a new mounting system would be necessary.

The original Winchester A5 scoped rifles had the rear scope block mounted on the flat portion of the rear sight base (photos: US Army & Steven Norton). The army would decline to pursue the implementation of this design, as detailed in the document above (document: Andrew Stolinski/Archival Research Group).

Aware of the army’s issues with the initial A5 scoped rifles, the Marines would choose to go to the private sector for a mounting solution. Designed by ballistics expert Dr. Franklin Ware Mann and produced in German immigrant Adolph Niedner’s gunsmithing shop, the “Mann-Niedner tapered blocks” would lead to a tightening effect with each shot fired, solving the persistent problem of contemporary scopes sliding forward on their blocks during recoil. The factory mounts that came with the A5 scope, referred to by Winchester as “#2 mounts,” would be modified by Niedner with the bases of the #2 mounts being cut off and new ones attached that could accept his tapered block design. In addition, durable turrets that had more positive ranging markers would be installed. Niedner had began a relationship with the Marines in the late summer of 1916, when officers and Marine rifle team shooters purchased his blocks and modified A5 scopes to have mounted on their rifles. These rifles were in turn used to train other Marines on the rifle team, which helped establish Niedner’s tapered block reputation to the Marine Corps. As the original sight mounting system proposed by Winchester for the A5 was not favored by any branch of the US military, the Mann-Niedner system provided a quality option for the Marines.

From a flyer given to the Ordnance Department, the specifications of the Winchester #2 mounts and mounting variations can be seen. Adolph Niedner would modify the #2 mounts to accept his tapered blocks (documents: Andrew Stolinski/Archival Research Group).

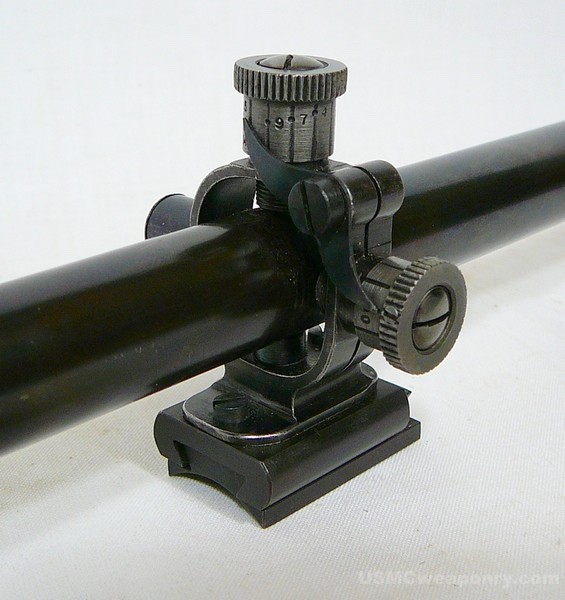

Close up view of the Mann-Niedner scope mountings and tapered blocks (Steven Norton collection).

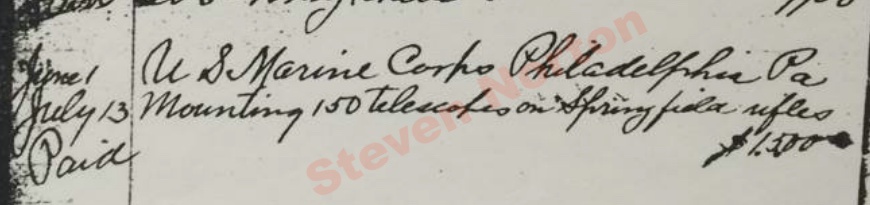

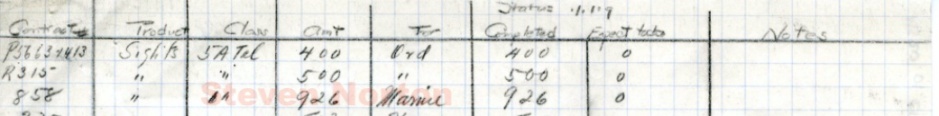

The ledgers of Adolph Niedner, showing the 150 rifles he converted into Mann-Niedner sniper rifles for the Marine Corps. These rifles used a tapered block system, and the Winchester A5 scope (documents: Steven Norton).

The FBI’s investigation into Adolph Niedner would cause an abrupt end to his work converting service rifles to sniper rifles (documents: Steven Norton).

In the late spring of 1917 following the American entry into WWI, the Marine Corps would contract with Adolph Niedner to drill, tap, and mount 1650 rifles with his tapered blocks and modified A5 mounts and scopes. Niedner had completed work on 150 rifles by June, and it was during this timeframe that the story of Marine A5 sniper rifles takes a most bizarre turn. Niedner, while at a local shooting range, allegedly made striking anti-American statements, proclaiming his desire for America to lose the war and that “he hoped that everyone who went to France would be killed and he would like to do what he could to bring it about.” Anti-German sentiment in the country was at a fever pitch, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation immediately took up the case. Follow up interviews revealed that Niedner was prone to make comments that he himself did not believe, and were outlandish at best. Though a German immigrant, Niedner was also an American army veteran, having served honorably for two enlistments in the cavalry, making his comments even more strange when juxtaposed to a history of honorable American military service. Ultimately, whatever the truth was in regards to the comments, the FBI investigation would prompt the Marines to have the remainder of their sniper contract fulfilled elsewhere.

In rare company: perhaps the only original Mann-Niedner A5 sniper rifle in private hands, the rifle pictured above was recently discovered. The serial number is thought to be 650844, but has not been confirmed due to the irreversible damage that would be caused by removing the long staked on block screws. A USMC contract A5 scope case named to Private William Ipson, and serialized to M1903 #650844 was sold several years back on ebay. Private Ipson was a school trained sniper with the 13th Marine Regiment, and would die of pneumonia in France. As of now, this rifle has by far the most USMC provenance of any WWI era sniper rifle to be found (Tyler Anderson/Ozark Machine Gun collection).

Private William W. Ipson was a trained Scout/Sniper. Like so many of his peers in 1918, he would be mortally stricken with pneumonia caused by the Spanish influenza. The scope case assigned to him and Mann-Niedner sniper rifle #650844 was observed several years ago (SRB file courtesy of Tyler Anderson).

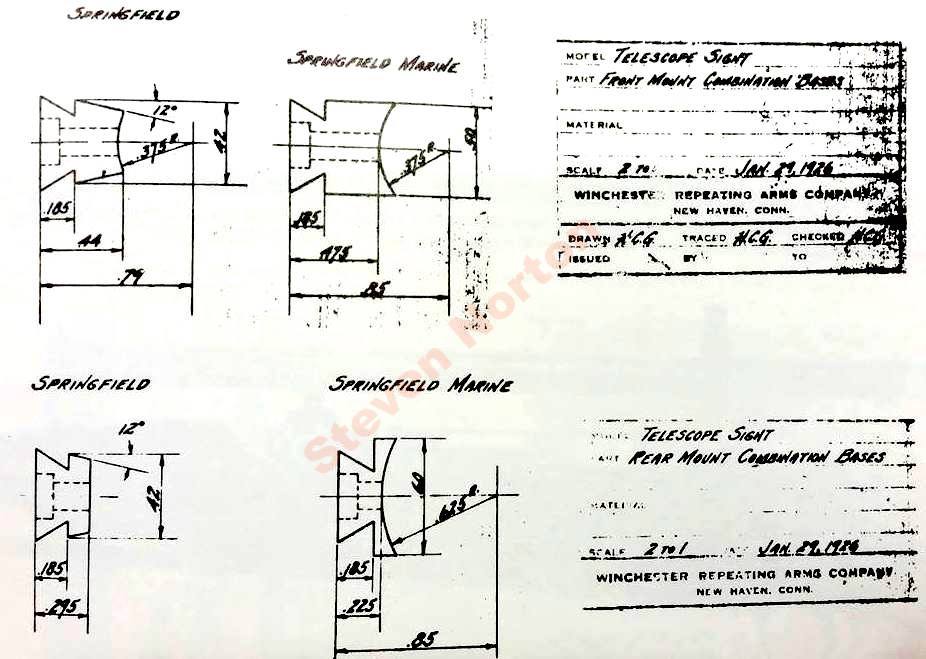

By July of 1917, the Marines had concluded their best option was to turn to Winchester for their sniper rifle needs and what would be an entirely different mounting system. The new design would correct for previously noted deficiencies and have the rear scope block mounted on the top of the receiver in the style of the Mann-Niedner rifles. Winchester’s standard #2 mounts would be used, and the newly designed blocks would be referred to in official Winchester documentation as “Springfield Marine” blocks. Eventually approved by Major (and later Commandant) Thomas Holcomb, the Springfield Marine blocks were considerably smaller than the Mann-Niedner type, and did not employ a taper to them. While the mountings were indeed quite different, the position of the scope relative to the eye of the individual Marine marksman as well as the operation of the scope in relation to the rifle was practically the same. This would allow for both variants of A5 sniper rifles to be used interchangeably at the operational level with little to no difference being observed by the shooter in regards to body positioning and handling.

Schematics for blocks made by Winchester (document: WRA c/o Steven Norton).

One potential point of confusion that would arise from dual versions of A5 sniper rifles being used at the same time would be the lack of standardized nomenclature in official documentation. The Winchester produced rifles and their mounting system would most often be referred to as the “Marine Corps mounting” in Ordnance Department documentation, which was previously believed to be in reference to the Mann-Niedner variants as they were also Marine Corps specific. However it is now clear they were referring to the Springfield Marine type rifles delivered by Winchester. In Marine Corps documentation, the Springfield Marine rifles are more ambiguous, with their Winchester origin usually being the point of identification. The Mann-Niedner system, while labelled in various ways, usually includes mention of the tapered design of the scope blocks and mountings. Neither A5 variant would have an official name in Marine Corps or Ordnance Department documentation, leaving context and key words as the only way to determine which particular type of rifle is being discussed. While this isn’t too difficult given the level of understanding we have today due to diligent examination of archival documents, it was not long ago that every mention of the Marine Corps in regards to an A5 sniper rifle was assumed to be describing a Mann-Niedner rifle. The Winchester built Springfield Marine rifles had managed to escape large scale recognition, but thanks to the research efforts of folks like Steven Norton and Andrew Stolinski we now have the ability to differentiate between the two in documents.

Winchester photos of one of their M1903 Springfield Marine A5 sniper rifles (photos courtesy of Steven Norton).

Springfield Armory #368496, a Springfield Marine M1903 A5 sniper rifle. Winchester drilled, tapped, and mounted 500 of these rifles for the Marine Corps and 900 for the army during World War One. Exceedingly rare, only a handful of the rifles are in private hands (Steven Norton collection).

During the Winchester sniper rifle mounting process, a challenge would manifest in the drilling of the receivers. Case-hardened receiver steel would prove too hard for the drill bits of that era to cut in to. The carbide drill bits of today had not yet come into existence, so Winchester (and presumably Adolph Niedner) would instead anneal the receivers precisely where they would drill and tap them. Using a very fine flame, the receivers would be heated just hot enough to accomplish the drilling process. This “spot annealing” technique has thus become a very useful tool to help further corroborate potential Winchester made Springfield Marine sniper rifles. The blued receivers on these rifles have allowed the annealing work to remain visible a century later, as one can still observe heat-induced discoloration.

In order to drill into the case hardened M1903 receivers and install Springfield Marine blocks (often referred to as the “Marine Corps mounting”), a fine point flame would be used judiciously. The army would later attempt to do this at base depots in France, but would not be successful (documents: NARA c/o Andrew Stolinski/Archival Research Group & Steven Norton).

The Marine Corps’ A5 sniper rifles garnered media attention during the summer of 1917 (New Smyrna News c/o of Steven Norton).

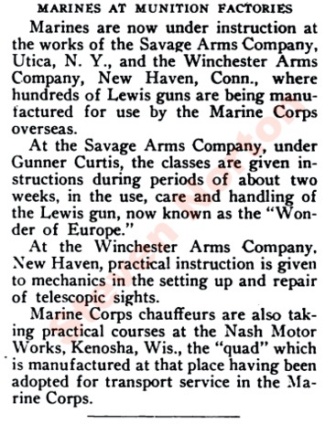

Marines underwent instruction on how to drill, tap, and mount Winchester A5 scopes on M1903s in-house at Winchester in 1917 (Man at Arms c/o of Steven Norton).

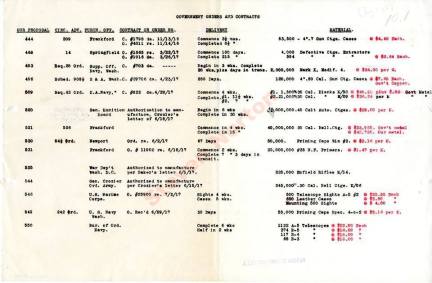

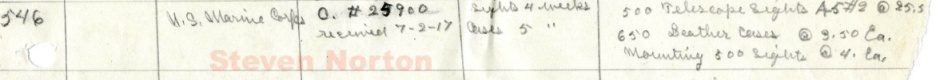

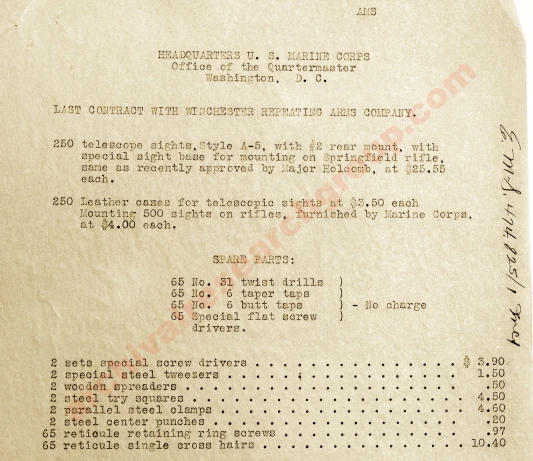

From invoices and ledger entries we are able to gain good insight into the Marines’ dealings with Winchester. The initial contract was for 500 service rifles to be drilled, tapped, and A5 scopes mounted, as well as providing 650 leather scope cases. 150 additional cases were ordered to cover the scopes on the Mann-Niedner rifles which had been completed by Adolph Neidner earlier that spring. Originally quoted by Winchester to be finished in four weeks (by the end of July), it took considerably longer to complete. Documents show us that the initial Marine contract would be split into two installments, which almost certainly occurred in order for some of the rifles and cases to be shipped while Winchester dealt with a backlogged workload. Like many companies that did work for the government at that time, Winchester was unable to handle the boom of contracts sent their way during the beginning of American involvement in the war. On top of this, bookkeeping was sloppy, eventually leading to federal auditing and censure in 1918. Despite the particularly poor records keeping, the dates of Winchester’s entries give us an indication of when the work would have been finished and the freshly built Springfield Marine sniper rifles obtained. While the invoice for the first installment of 250 rifles and 400 scope cases has not yet been found, the invoice for the second consisting of 250 rifles and 250 scope cases has, and is dated October 9th, 1917. This makes clear the first contract would already have been finished by that time. The second installment would be paid by the Marines on November 17th, 1917, thus completing the entire initial contract.

Ledger entries showing the initial contract with Winchester to drill, tap, and mount 500 rifles with A5 scopes, and provide 650 leather scope cases. The contract would take longer than the four weeks as quoted, and would be split into two installments (documents: WRA c/o Steven Norton).

The last half of the initial 500 rifle/650 case contract the Marines had with Winchester (document: Andrew Stolinski/Archival Research Group).

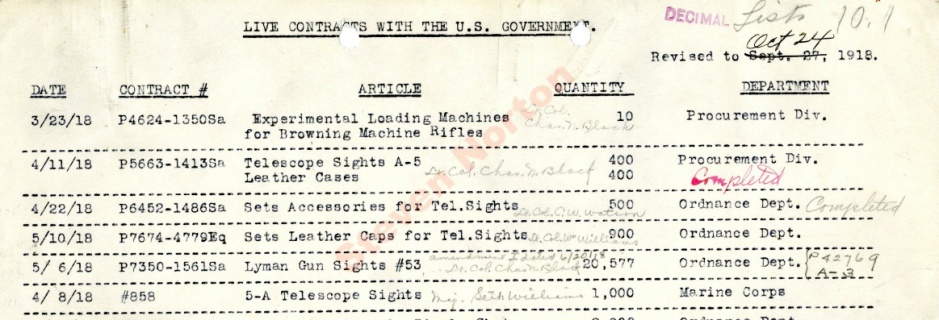

As the buildup of American troops in France began in earnest, the 5th Marine Regiment would be dispatched to join Major General John J. Pershing’s fledgling American Expeditionary Force (AEF). Soon to follow, the newly minted 6th Marine Regiment would join them, the two forming the 4th Marine Brigade. This all-Marine brigade would join the army’s 2nd Infantry Division, and thus fall under army command. Due to this, the Marine A5 sniper rifles would become intertwined to some extent with the army. The command structure dictated the Marines would use the same repair and supply depots as the rest of the AEF. It is here that we get a few glimpses into a logistical system that shows a potential redistribution of weapons amongst the services. An order from General Pershing to the 5th Marine Regiment on September 30th, 1917 dictates the delivery of ninety A5 sniper rifles to Ordnance Advance Depot No. 1, twenty of these to be delivered to an Ordnance Department representative. Through a subsequent communique it is clear that the twenty rifles were set aside for a British-run sniper school, where the allies would send their marksmen for further training. Beyond this, the large “base depots” as they were called would provide a central hub for the careful repair of AEF sniper rifles. Regimental armorers did not have the proper facilities to effect repairs, especially those to the Winchester A5 scope itself. These higher level repair facilities would fall wholly under army command, but Marine weapons would be serviced there. The same base depots would also receive shipments of weapons for the Marines, including the Springfield Marine A5 sniper rifles that were sent to them directly from Winchester. While it is unclear if any of the Springfield Marine sniper rifles had arrived in France by the time of Pershing’s order, it is nearly certain most (if not all) 150 Mann-Niedner sniper rifles had arrived with the 5th Marine Regiment. If the Springfield Marine rifles were still yet to arrive, roughly sixty Mann-Niedners would have been left in Marine possession, which is more-or-less in line with the thirty-six sniper rifle per regiment allotment assigned by General Pershing for the American Expeditionary Force. The Marines were due to receive many more sniper rifles, and we know at least some of the Springfield Marine rifles were in France in 1917, as evidenced by army documentation and Signal Corps photographs. This begs the question as to how many went to Marines on the front line, and how many could have been divvied up by higher echelon American Expeditionary Force commanders and given to divisions that were without sniper rifles altogether. Archival documents do show divisions drawing rifles from Ordnance Depots when needed, and it is possible that sniper rifles were stored there until needed. Being able to allot sniper rifles as required would have been helpful to the army, which was still using the aging Warner & Swasey sniper rifle and short of sniper rifles altogether. Although the army was in the process of developing a new sniper rifle utilizing the M1917 “American Enfield” service rifle and a revised version of the Winchester A5 scope, progress had been slow. Referred to as the M1918 or M18 in army documentation, the brass hoped the Warner & Swasey sniper rifles would tide them over until the new M1918 scoped rifles were operational. At some point in late 1917, the army would be told they would not be able to receive an additional 4000 Warner & Swasey scopes they had previously requested. Simultaneously, the feasibility of the M1918 mounted rifles came into question as the prices were to be higher than expected. The army had become accustomed to the Marine Corps A5 sniper rifles that had arrived at the base depots, and the Winchester variants that had recently been shipped there presented an opportunity for a sorely needed stop-gap as combat operations were on the horizon. In January of 1918, the army decided to expediently remedy their shortage, and requested Winchester to produce for them A5 sniper rifles exactly like the ones they had for the Marines. Production would begin not long after, and two contracts for a total of 900 A5 sniper rifles would be executed.

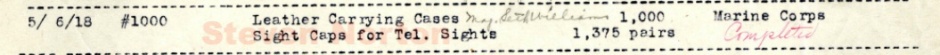

Follow-on Marine contracts with Winchester would be for 1000 A5 scopes, of which 926 would actually be procured, as well as for replacement parts. The army would also have 900 M1903s drilled, taped and mounted with Springfield Marine blocks to cover the other sniper rifle options that had not come to fruition (documents: WRA c/o Steven Norton).

Incredible trove of documents showing the army’s decision to adopt Springfield Marine variant sniper rifles (documents: NARA c/o Andrew Stolinski/Archival Research Group).

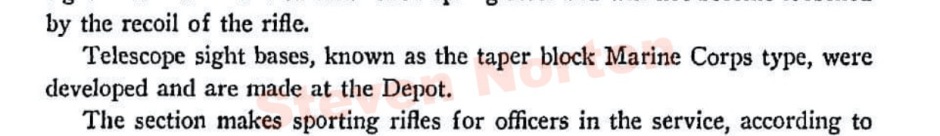

1918 would bring about yet another variation in Marine A5 sniper rifles. The previous summer, the Marines had become convinced they would be best served by internalizing the sniper rifle conversion process, likely due to the Adolph Niedner investigation fiasco. To remedy this, in July of 1917 the Marine Corps had sent armorers to Winchester to learn how to do the work of drilling, tapping, and mounting themselves, as well as being trained in the repair of A5 scopes. In-house sniper conversions by the Marines would not have began before very late 1917 or early 1918, and 1000 A5 scopes and cases were ordered from Winchester for these rifles . Interestingly, the Marines would revert back to using the Mann-Niedner system for their sniper builds. While no documentation on their reasoning for doing so exists, it seems likely this was done due to superior field performance. The Marine quartermaster files for this era have yet to be found (and may no longer be in existence), but documents from 1918 mention the Marines producing tapered blocks at the Philadelphia Depot for their sniper rifles. Currently, there is no way to identify with certainty the difference between a tapered block A5 sniper rifle made by Niedner or by the Marine Corps. Current rough speculation is that the handguards might hold the key. The previously posted photo of a Marine sniper with the 4th Marine Brigade in France is very likely to be of a Niedner made rifle, and the group photo of Marines at a Quantico sniper school in 1918 is likely to show Marine Corps made rifles. The handguards between the two do look a little different, but again this is just a loose observation and a lot of guesswork. The reasons for this could be many, and the Marines likely did the woodwork on the Niedner rifles, but a difference between the two suggests an evolution in the process and could be helpful establishing a timeframe. The tapered Mann-Niedner blocks dictate the scope must be placed on the block from the rear in order for the design to work, and the rifles pictured in the sniper school photograph have a much more generous amount of room behind the front block to aid in the mounting process. Perhaps this is due to the small amount of room for rearward mounting as seen on the Mann-Niedner rifle pictured in France being insufficient, and a modification in handguard design having occurred. While speculation might be all we have for the moment, intensive archival research efforts over the last few years have rewritten much of the Marine Corps weapons story, it wouldn’t be surprising if future documents will shed more light on the differences between these two variants of Mann-Niedner A5 sniper rifles.

Annual report to the Commandant briefly mentioning the internal production of Mann-Niedner tapered scope blocks (courtesy of Steven Norton).

Marine sniper school class during WWI, it appears all are armed with the Mann-Niedner variant (photo: USMC).

Mann-Niedner variant sniper rifles in France during WWI (photos: NARA c/o Steven Norton).

Springfield Marine variant A5 sniper rifle in the hands of a Marine sergeant in France, 1917 (photos: NARA c/o Steven Norton).

Documents detailing the sending of Marine sniper rifles to Ordnance Depots in France, and how divisions wold draw rifles from there as needed. It is possible the army used some of the sniper rifles that were Marine Corps property due to the shortage they faced. Also included are the table of organization for AEF regiments to have roughly 36 sniper rifles in total; the Marines had more than enough to spare (documents: NARA c/o Andrew Stolinski/Archival Research Group).

The Base Depots of the American Expeditionary Force played a large role in the supply, maintenance, and repair of all US WWI sniper rifles, including those of the USMC (documents: NARA c/o Andrew Stolinski & Man at Arms c/o Steven Norton).

Operationally, the valor of Marines snipers in WWI is well documented. From the onslaught of combat, Marine snipers would take to eliminating German officers and strongpoints, usually at tremendous risk. The first American sniper to be awarded the Medal of Honor was Marine Corporal John H. Pruitt of the 6th Marine Regiment, his exploits and those of many other American snipers in WWI can be found in this excellent article by army Major John L. Plaster for American Rifleman. Though relatively new, and much more deadly than in past conflicts, snipers would be employed effectively by American commanders despite the type of combat they faced. Due to the missing quartermaster files from that era, it is hard to say what issues in regards to the rifles were to have arisen, and what the Marines thought about their equipment. It seems logical that the experience would have been similar to that of the army, and luckily their files are readily accessible in the archives. Thumb screws on the Winchester Springfield Marine type rifles were at a premium, and by late July of 1918 in desperate need of replacement as they seemed to come loose easily and be lost. Loose thumb screws would present another issue, as the slightest movement in the mountings on the blocks would throw off a sniper’s zero. It is likely these issues played a noteworthy role in the Marine Corps’ decision to switch back to the Mann-Niedner system when they began production of their own rifles.

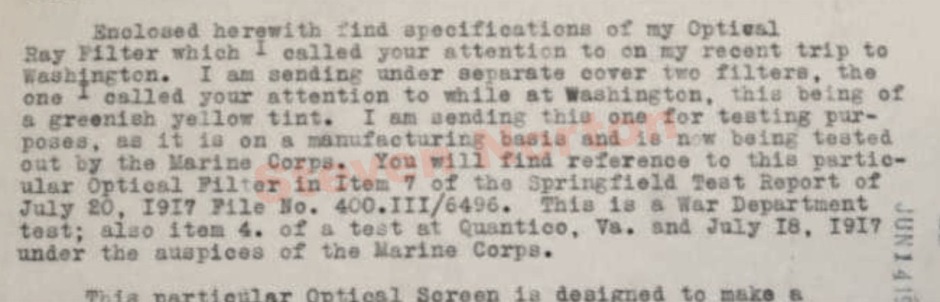

Marine with A5 sniper rifle in France, most likely the Winchester made Springfield Marine type, possibly posed at some point after the Battle of Belleau Wood as indicated by writing on the bottom righthand portion of the photo. Trees in the background appear to be debarked as well. Interestingly, there appears to be a cover on the A5 scope; the Marines explored the “Optical Ray Filter” for use in 1917, as noted below (document and photo: NARA c/o Steven Norton).

Following the cessation of WWI the A5 sniper rifle’s story goes a bit dark, as the documents for this era are unfortunately lacking. Some of what can be gleaned comes through Marine Corps rifle team documents, and the various types of scoped rifles they employed for long range matches. Both Mann-Niedner and Springfield Marine blocks can be seen being used in pictures, as well as newer designs like the Fecker and Stevens scopes and mounts. As for the WWI produced sniper rifles themselves, we know some stayed with the infantry. A 5th Marines equipment document from operations in Nicaragua shows a cluster of A5 sniper rifles in use, the serial ranges spanning a large portion of the Springfield Armory 600k serial number range. While it is unknown if these are Springfield Marine of Mann-Niedner variants, the serial number clusters are favorable to both options, as existing examples of both types have been found very close in range. Unfortunately, as of now there is very little else mentioned of A5 sniper rifles during the interwar years, but by the late 1930s with war again on the horizon, documents do shed some light on the subject. Listed at the Philadelphia Depot in an April 1938 quartermaster’s report are 141 rifles fitted for telescopic sight, 538 receivers drilled for telescopic sight bases, and three receivers fitted for telescopic sights. While there is no mention of what type of scope these rifles were drilled or fitted for, they would have overwhelmingly been the remnants of those produced in WWI. Most are shown as having been stripped down to the receiver, for purposes unknown but likely as parts donors due to a shortage of stocks and small parts amongst standard service rifles. While there there is no documentation showing additional sniper rifle production in the interwar years, it is possible there were small amounts of various other types of rifles included in these figures. An interesting document from the 4th Marines in the 1930s shows a request for additional eyepieces for their Warner & Swasey scoped rifles. While it is possible these Warner & Swaseys were from the initial small compliment the Marines received in 1909, they also could have been obtained in any other number of ways. These are the exception though, and the 682 scoped rifles/receivers on hand in the report would have primarily been drilled and taped for blocks to mount the A5 telescopic sight. On top of these rifles and receivers, some would have remained in the hands of various infantry units, as the 5th Marine Regiment equipment lists from Nicaragua show that they continued to play a role operationally.

Documents showing Marine M1903 A5 sniper rifles during the interwar years, the usual term for them being “Rifle, Cal .30, fitted for telescopic sight” (Documents: Tim Plowman/NARA).

By 1940, it was apparent a new sniper rifle was needed to replace the aging A5 mounted rifles (documents: Tim Plowman/NARA).

With World War II looming on the horizon, the Marine Corps began to search for their next sniper rifle. Leading optical companies Noske, Lyman, Weaver, and Unertl were consulted in late 1940, with tests concluding the following spring. The results of the Marine Corps equipment board testing determined the optimal sniper rifle would be the Winchester Model 70 mounted with a J. Unertl 8x scope, and procurement of both was recommended. Simultaneously, the 1st and 2nd Marine Divisions were outfitted with 20 A5 sniper rifles each for the initial training of Scout Snipers. A sniper school was set up at Camp Elliot in San Diego, providing the instruction for successful employment of the A5 sniper rifle to a new generation of Marines.

As the United States entered World War II, Marine marksmen would once again find the figure of the enemy in the crosshairs of the A5 scopes their father’s generation had used in France. The Marine Raiders, a new tip-of-the-sear assault force would be issued 40 A5 sniper rifles prior to their departure for combat in the South Pacific. The newly formed 1st Marine Division, which included the 5th Marine Regiment, would have had an unknown number of A5 sniper rifles in their possession form their initial issue during World War I; it is unknown if these rifles had seen any updates or overhaul or not, as the documentation for them is scarce. The A5 sniper rifle would be well received on Guadalcanal, and the demand for a better sniping solution fervently requested by field commanders. While only one photograph of a Marine sniper on Guadalcanal exists, we can clearly see a Hatcher Hole and Mann Niedner scope on the rifle, showing that at minimum some of these rifles had been rebuilt prior to WWII issue.

Documents detailing the A5 sniper rifle story leading up to and early in WWII (documents: Tim Plowman/NARA).

Corporal Anthony Di Cristofaro of 3d Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment on Guadalcanal with a Mann-Niedner A5 sniper rifle (photo: NARA).

The only documents clearly showing Marine A5 sniper rifles in weapons counts are those of the 2nd Raider Battalion (documents: Tim Plowman/NARA).

Most of the photos that exist of A5 sniper rifles in WWII are in the hands of Marines training stateside. The highest quality photo, which allows much to be speculated about the rifle itself, is of a 2nd Marine Division sniper training in New Zealand in early 1943. It is a near certainty the rifle pictured was one of the 20 given to the division for training purposes the year prior. By this time the Marines had begun production of the M1903A1 Unertl sniper rifle, having determined that the benefit of parts interchangeability outweighed the slight marksmanship edge the Winchester Model 70 offered. By mid 1943, the Marine divisions were receiving these new rifles, but the A5 would continue to play a role throughout the end of the war. Stateside sniper schools would rely heavily on the A5, some rifles pictured having pistol gripped C-stocks to better familiarize Marine marksmen with the M1903A1 Unertls, which more often than not came in C-stocks. Weapons counts throughout WWII would fail to distinguish between Unertl or A5 mounted sniper rifles, as such it is impossible to know how long they served on the line. With no orders stating such existing, it is likely some A5s served in combat units for the duration of the war.

Corporal Donald O Radke, Recon & Scout Platoon, 3d Battalion, 9th Marine Regiment during the Battle of Bougainville (photo: USMC).

Special page acknowledgments: the story of the A5 sniper rifle has really come into focus in the last few years thanks to the hard work and tireless research efforts of Steven Norton. Just like the fine details behind the Unertl sniper rifle, Steven spent countless hours and many dollars to mine archives throughout the nation, and this section would be far smaller if it wasn’t for him. Andrew Stolinski as well has spent many, many hours digging in the National Archives, with a lot of new A5 documents being found in his visits. Andrew is the most active weapons-centric archival researcher today, and shares his finds on his website, www.archivalresearchgroup.com. I can’t recommend a subscription to his site enough!