The chaotic realities of trench warfare in World War I exposed a flaw with the M1903’s sights: they were difficult to acquire in harsh combat environments. This prompted the decision to create a more “combat friendly” sight system for the M1903. The solution would take the form of a thicker front sight blade and larger rear peep, emulating the easy target acquisition of the US M1917 rifle’s sights. The M1917 was used primarily by army troops in the war, but also to some extent with the Marines, and was praised for sights that infantrymen found to be superior to those of the M1903. While not a perfect rifle, the M1917 did invite improvement in the M1903’s standard issue .06 width “#6” sights, and in response the Marine Corps’ .10″ width “#10” sight system was born.

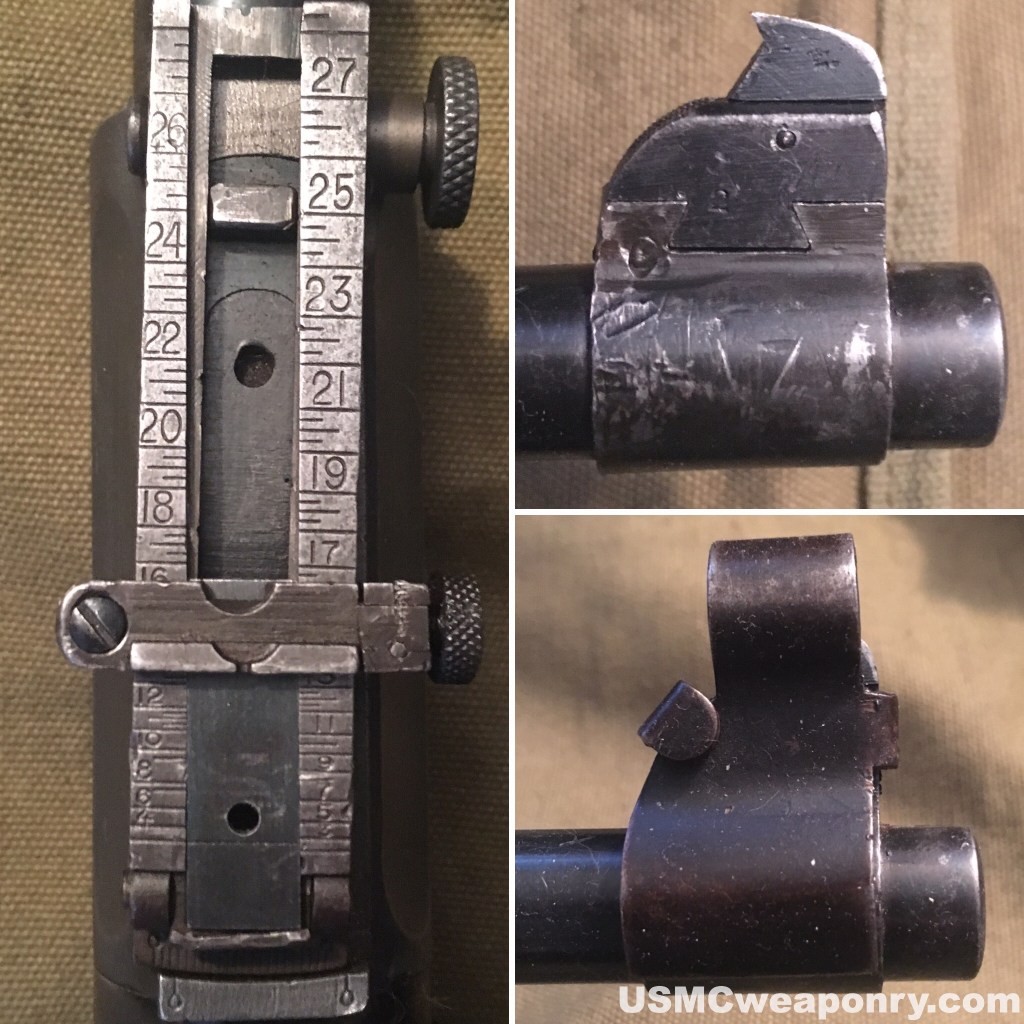

#10 sight system during testing and development at the Philadelphia Depot of Supplies (NARA).

The unique #10 sight system would serve on Marine M1903s during the interwar years (Plowman collection).

The #10 sight system would include a taller, wider front sight blade, a large, solitary peep on the slide, and a vastly improved, larger front sight cover which no longer restricted the shooter’s field of view. The battle sight zero (BZO) was also changed to what the Marine Corps believed was a more appropriate 200 yards. Although the #10 sight system was designed by the Marines at the Philadelphia Depot, it would be manufactured at Springfield Armory. An order for 57,000 front sights, slides, sight covers was filled in 1919. While suited very well for the front, it was soon noticed to decrease the accuracy of Marine recruits qualifying at Parris Island. The officers of the rifle range detachment conducted thorough studies on the loss of accuracy compared to the range friendly, production standard #6 sights, but ultimately it was decided that instruction could manage the problem. The #10 sight system was to stay for the immediate future.

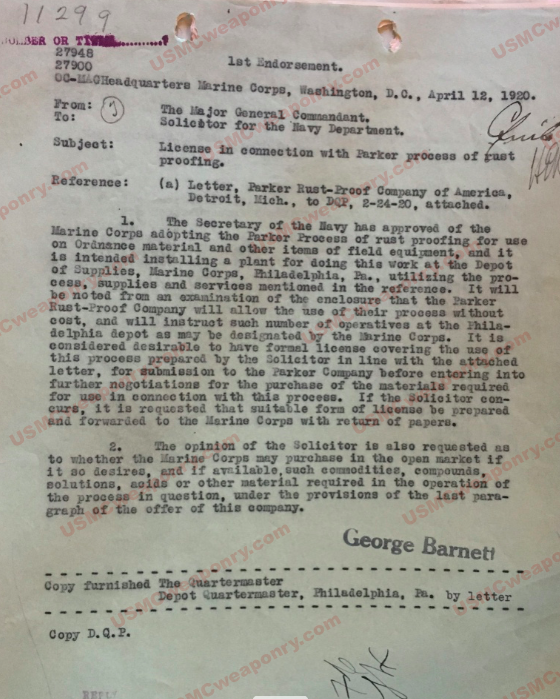

Parkerizing would dramatically increase finish durability and longevity, with the Marine Corps adopting it following WWI (NARA).

Sights weren’t the only concern following the war as many M1903s had worn out barrels. With corrosively primed ammunition being the standard of the era, soggy French trenches led to barrels needing replacement and rifles light on finish. In 1920 the Marines took action on both, requesting barrels from Springfield Armory and adopting the Parker process to refinish rifles. “Parkerizing” increased finish durability and was particularly beneficial to the Marines, as their operations tempo was higher than that of the other US service branches.

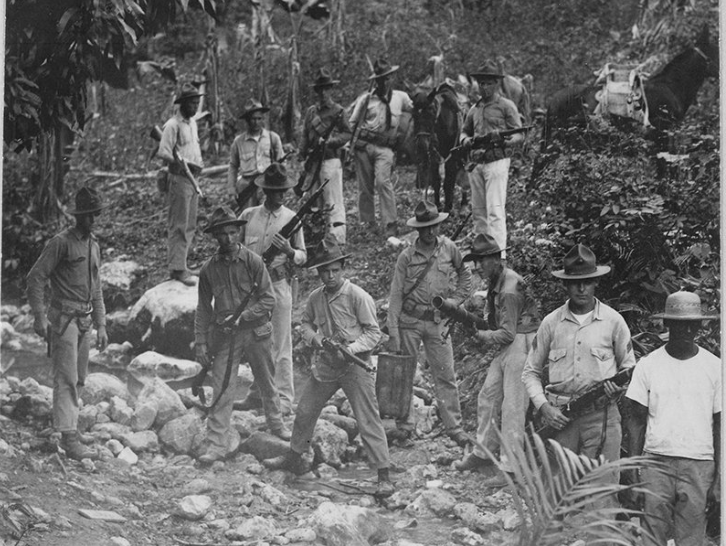

Marines in action in the Dominican Republic and Haiti (NARA/USMC).

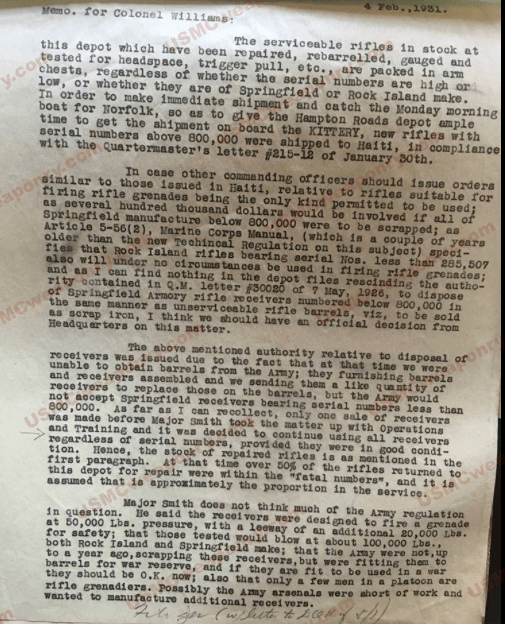

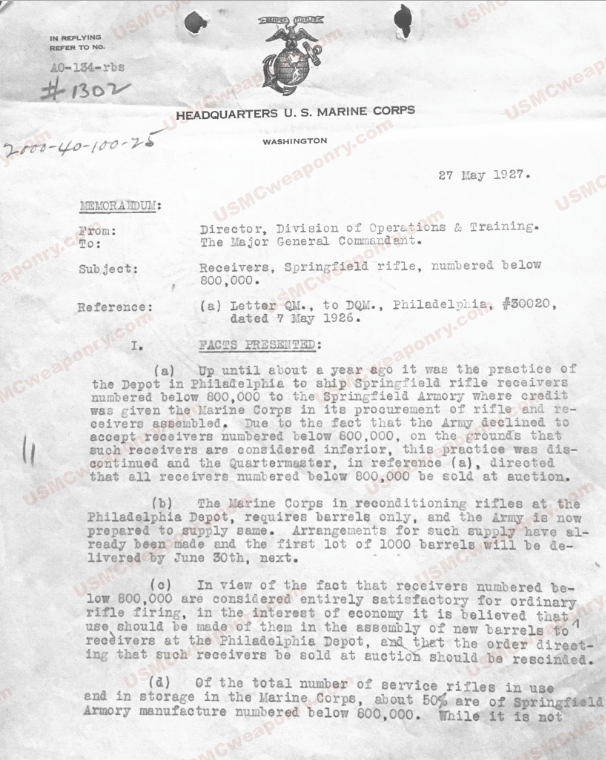

By 1926, it was becoming clear there was a problem with the hardness of some M1903 receivers. It was discovered that prior to 1918 armory personnel had forgone using instrumentation when newly forged receivers were heat treated, choosing instead to “eyeball” them to judge when the process was complete. Despite their expertise and skill, this shortcut led to some receivers being improperly exposed to the high hardening process temperatures. Overexposure caused receivers to become brittle and susceptible to breakage under pressure; underexposure would leave them soft and prone to premature headspace wear. The severity of this issue would be furiously debated by the Ordinance Department, and continues to this day amongst collectors. More than a few officers and ordnance personnel believed receiver breakage was due to faulty ammunition. Others believed it was Springfield Armory exaggeration, as they wanted to keep working during the Great Depression. For their part the Marines would find a middle ground. Rifles that would be expected to fire rifle grenades were required to be 1918 or later production, but standard ammunition was deemed safe for all M1903s.

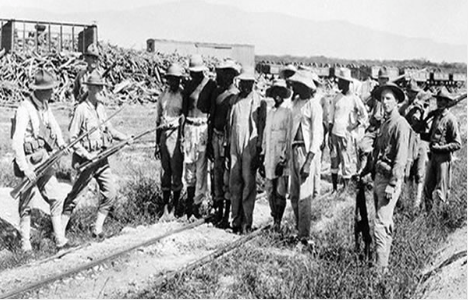

Marines in combat in Haiti (NARA).

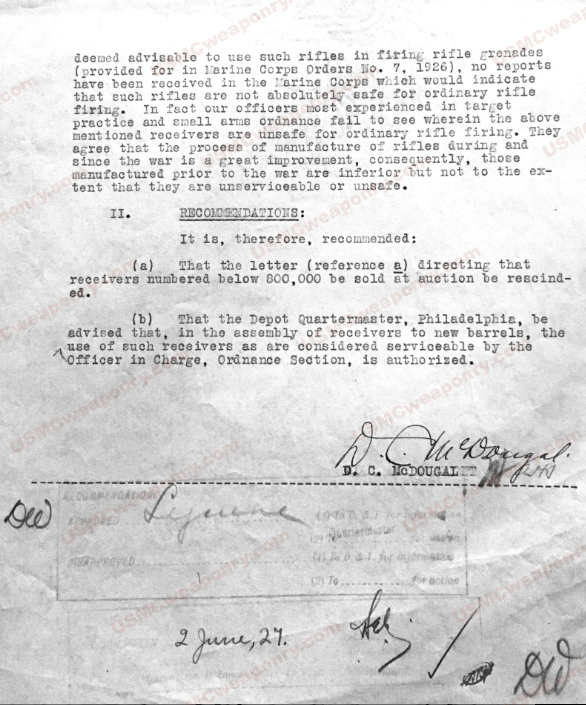

In 1926 the Marine Corps needed barrels for overhaul, but Springfield Armory and Rock Island Arsenal had none available. It was agreed that the Marines would instead send in worn out barreled receivers for a partial credit, and receive a fresh barreled receiver in exchange. As receiver hardness issues were now being addressed, Springfield Armory would only send barreled receivers made later than serial number 800,000 or those made by Rock Island Arsenal, as it was initially believed the heat treatment deficiencies were unique to Springfield Armory. This plan would be amended before any exchanges took place, as further examination found Rock Island Arsenal receivers to be just as faulty. The updated exchange policy would deem Rock Island Arsenal receivers under serial number 285,507 as unsatisfactory. All Marine M1903 “Unders” as the Marines called them would be turned in for no credit whatsoever, and would be replaced at cost with an “Over” barreled receiver. Today, Over and Under receivers are most commonly referred to as “high number” and “low number”, respectively. When encountering a Marine rebuilt M1903, the likelihood of finding one in the high number range is far greater, certainly due to this exchange. At minimum 10,000 barreled receivers were exchanged, with about two thirds of those sent in by the Marines being low serial numbers. Unfortunately for collectors, many of the low numbers exchanged would have been veterans of World War I combat, thus reducing the likelihood of coming across an example today. On top of the exchanges, one auction of an unknown amount of low number receivers was held by the Marine Corps, as indicated by National Archives documentation.

Directive to auction off low number M1903 receivers, referred to by the Marine Corps as “Under’s” in correspondence (NARA).

Not all low numbered receivers would bear the same fate, as just a year after the exchange program began the Marines terminated it. Due to a combination of cost concerns and the belief that low numbered receivers would be fine for regular rifle firing duties, the Marines decided instead to recycle all receivers and instead obtain new barrels, which were now available from Springfield Armory. Between 5,000 to 10,000 barrels a year would be procured for the next five years, allowing the Marines to significantly overhaul rifles that were wearing out. The combination of the late ’20s barreled receiver exchanges and subsequent barrel orders are quite evident today, as many USMC M1903s are observed with 1927-1932 dated Springfield Armory barrels.

USMC Rock Island Arsenal M1903 #324219 documented to the 2nd Marines in 1926 (Plowman collection, documentation by Andrew Stolinski & Archival Research Group).

The Marines’ freshly overhauled M1903s would not stay new for long, as ongoing “banana war” conflicts saw many Marines being rotated in and out of the Caribbean and Central America for duty. The 2nd Marine Regiment kept a presence in Haiti, which the US had occupied since 1915. The 11th Marine and 5th Marine Regiments would conduct operations in Nicaragua. The wear and tear from these conflicts coupled with the new directives from Springfield Armory led to more low number M1903s being replaced. Marine Corps policy stated low number receivers were unsafe for firing rifle grenades. The only Marines using rifle grenades were Marine infantrymen, and a directive in the late 1920s ordered Marine “grunts” to exchange any low numbered rifle. Some of the most serial number rich documents found have been from the 2nd and 5th Marines exchanges. The practice of issuing active infantry Marines high number rifles anytime possible would continue through the end of the M1903’s service.

Marines with their rifles in Nicaragua; Marine posing with his M1903 during duty in Haiti (USMC).

The tropical environment deployed Marines faced was notoriously tough on barrels and stocks, and the archives are rife with Marines being docked pay to replace unserviceable barrels. This was standard procedure as rifles were issued to the individual Marine rather than a unit, a practice which continued until very late in World War II. To combat tropical humidity, some Marines decide to take matters into their own hands and apply a shellac to their rifle stocks. While this was successful at reducing the swelling of the stocks in between periods of rain and heat, Marine Headquarters objected to the lack of weapons uniformity. These stocks were ordered to be either stripped of their shellac by the individual Marine or sanded down at the Philadelphia QM Depot. Despite the order, the remnants of shellac can be observed on some stocks to this day.

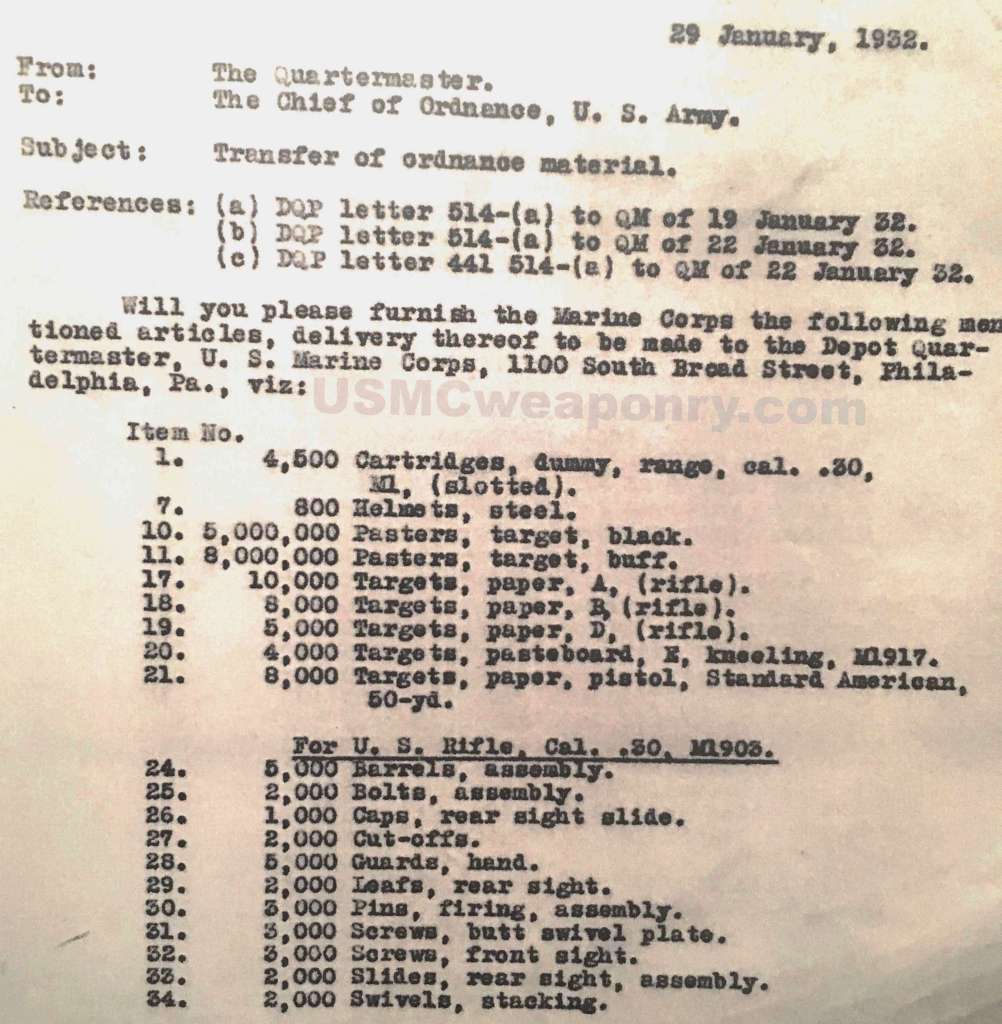

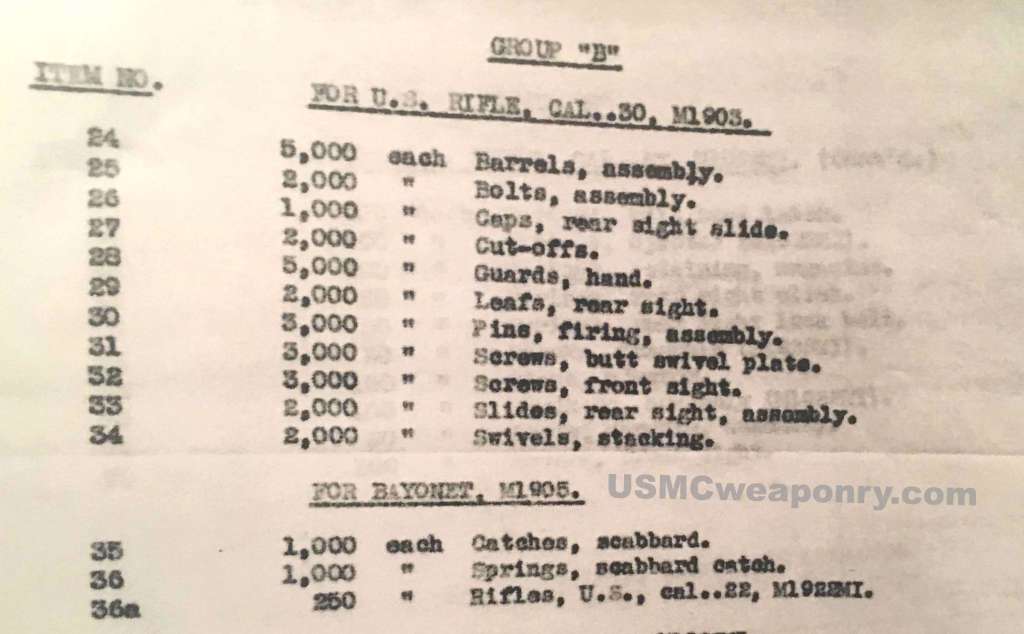

One of many order forms sent from the Quartermaster of the USMC Depot of Supplies in Philadelphia to Springfield Armory. After long campaigns in Nicaragua and Haiti, the Marines were once again in need of barrels, stocks, and small parts (NARA).

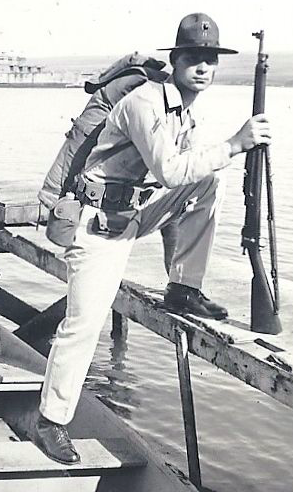

A Marine marksman with his M1903 (photo: NARA).

As the Banana Wars wound to a close, the years of 1931 and 1932 witnessed another major refitting similar in scale to the efforts of 1926-28. This would conclude major overhaul for the M1903 until later in the decade, but other significant changes were in the works. The following decade would see the USMC M1903 transform into the most recognized version itself, as a multitude of major modifications lay ahead.

6th Marine in China during the interwar years (http://www.chinamarine.org).