The mid 1930s would usher in many significant changes to the Marine Corps’ M1903s, culminating in the iconic WWII USMC rebuilds that are so well known today. Archival findings have shed light on the reasons behind the modifications that make USMC M1903s stand out from those used by other branches. The story of the WWII USMC M1903 begins in 1935, where the heavy influence of the Marine Corps Rifle Team would lead to the final evolution of the sighting system.

The Marine rifle team in the 1930s drove many M1903 policy decisions. Noticeable in this picture are the bright bolts of National Match rifles and new pistol gripped C stocks, which rifle teams service wide adopted in the late 1920s (NARA).

A Marine detachment performing rifle drills on a battleship in the 1930s (NARA).

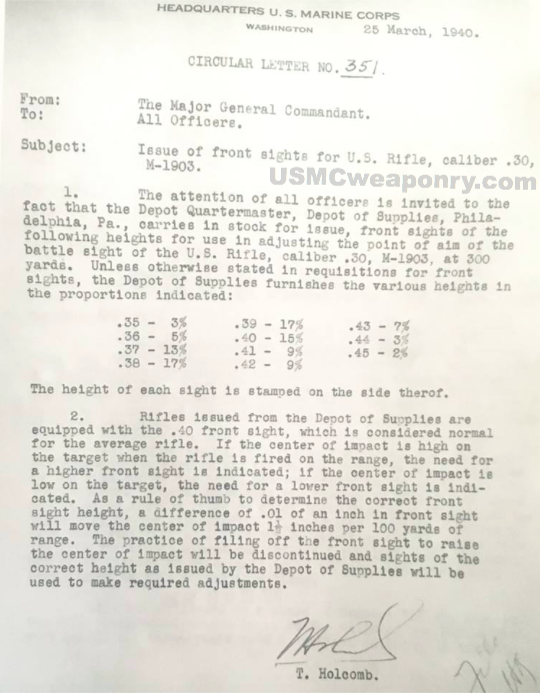

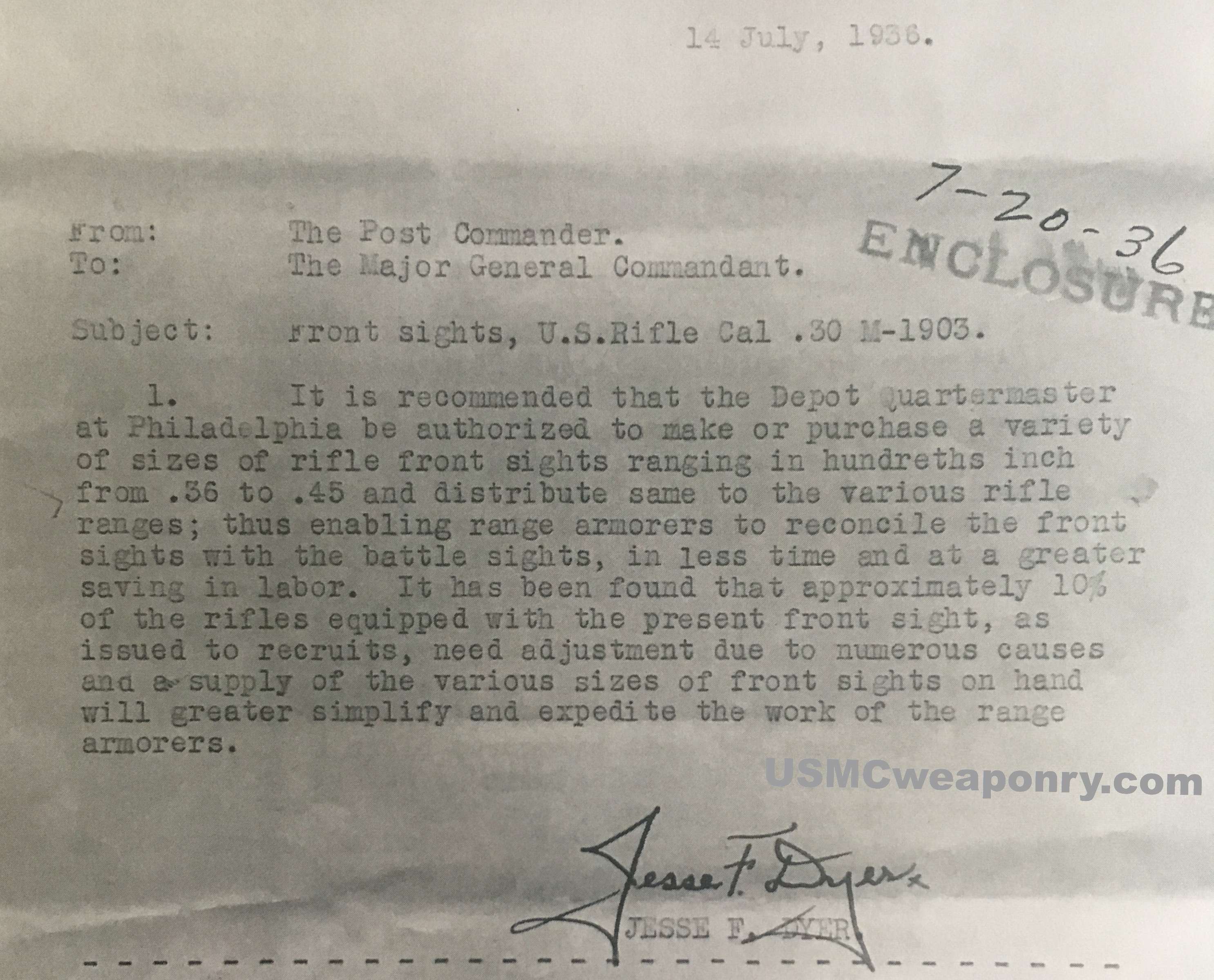

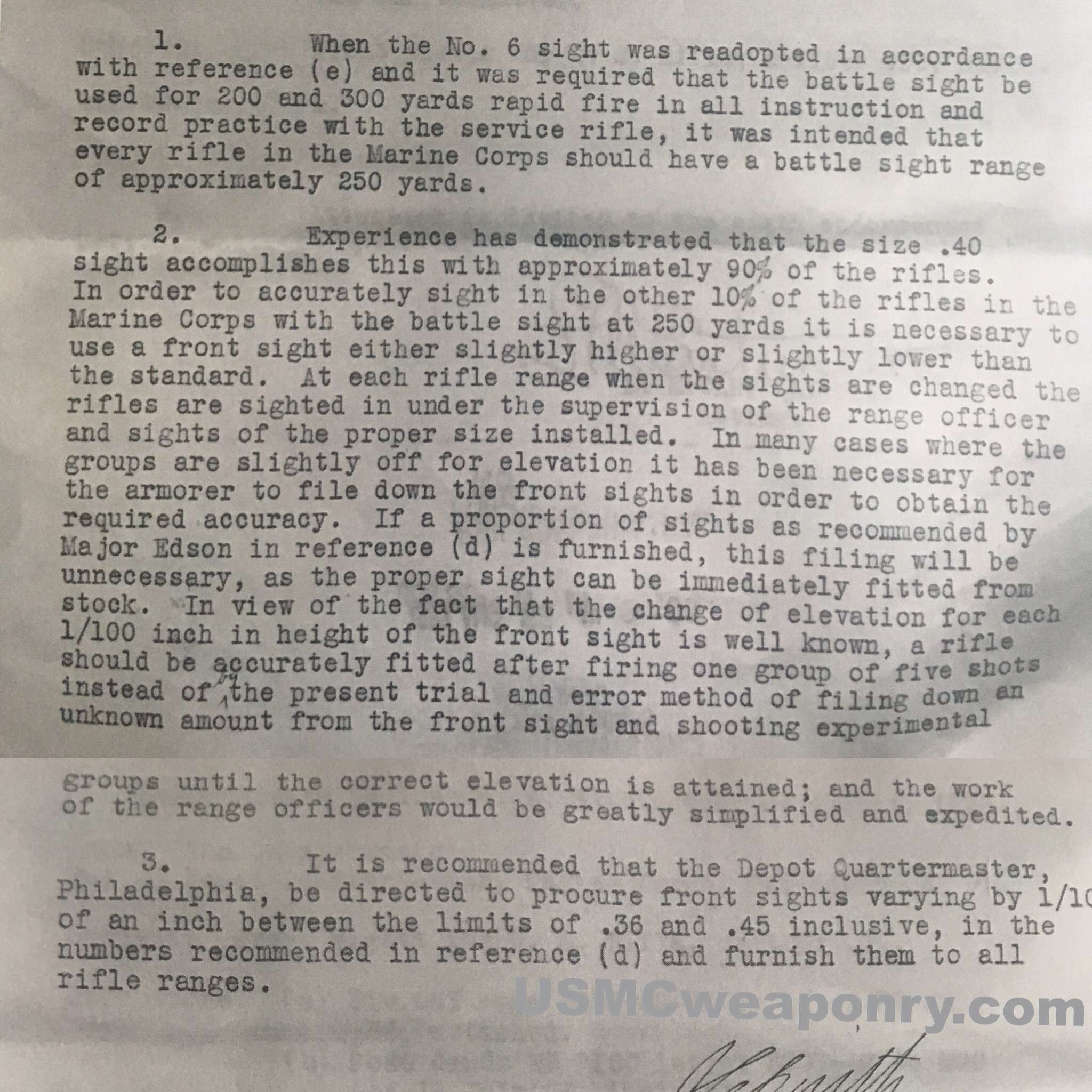

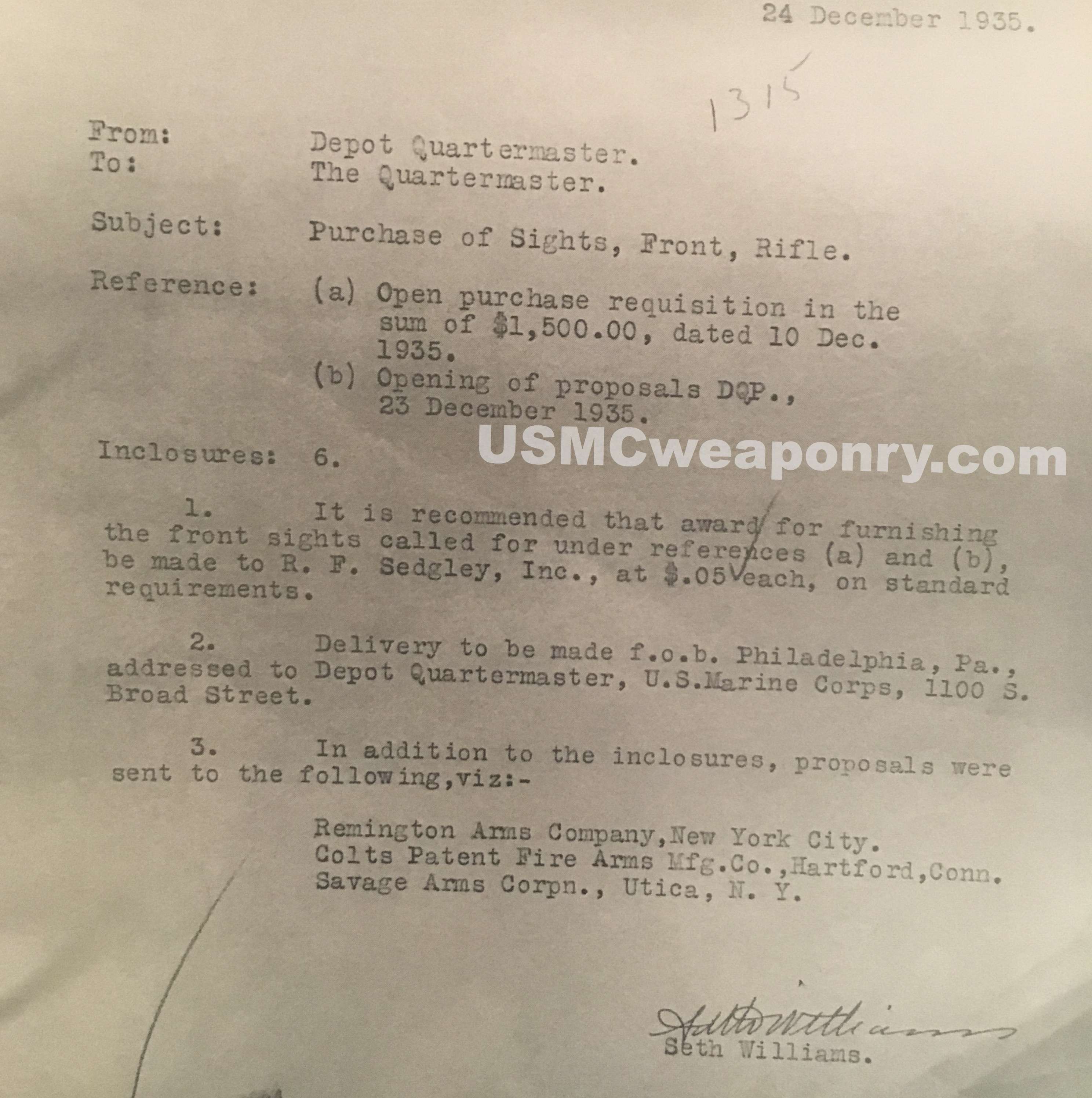

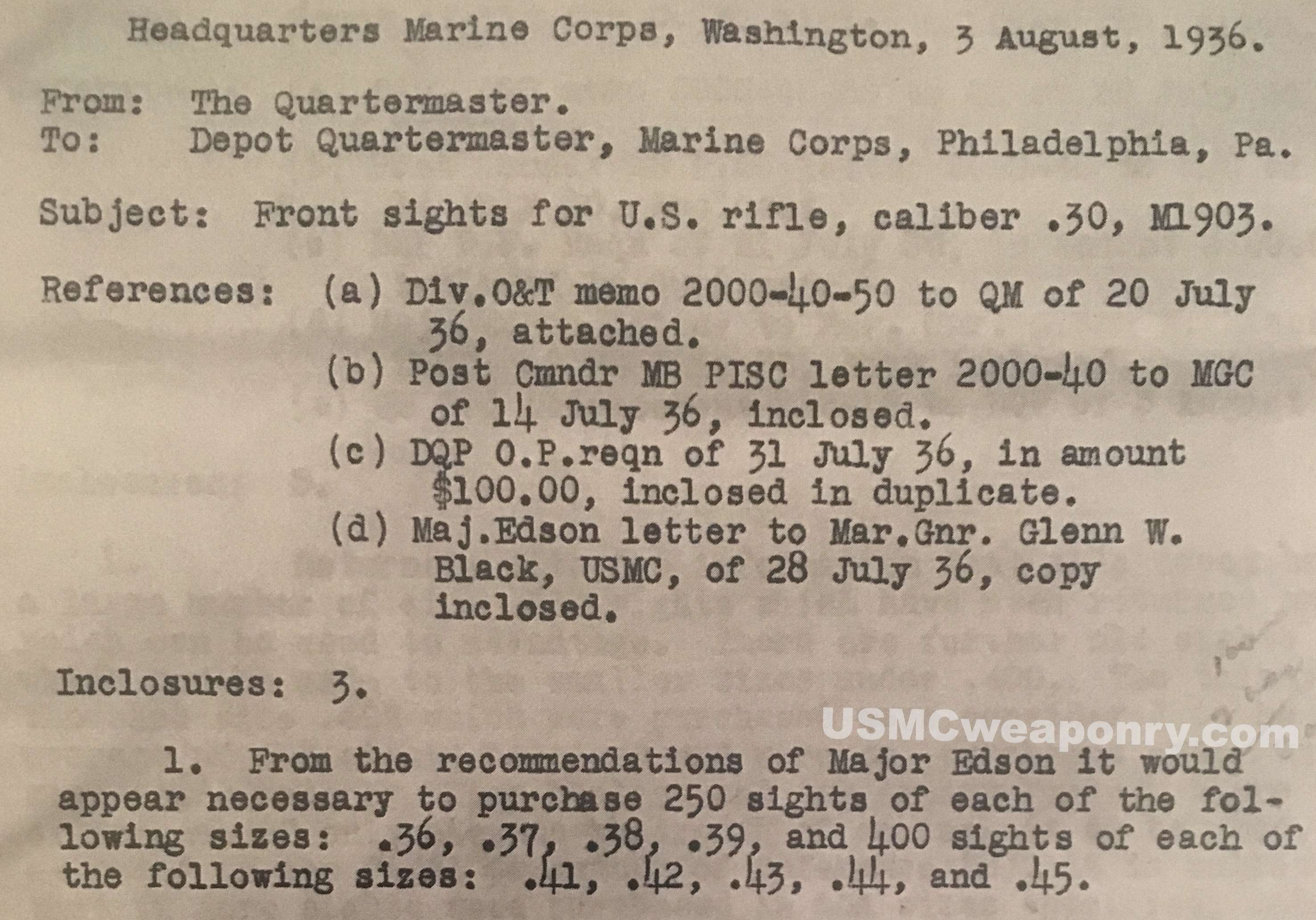

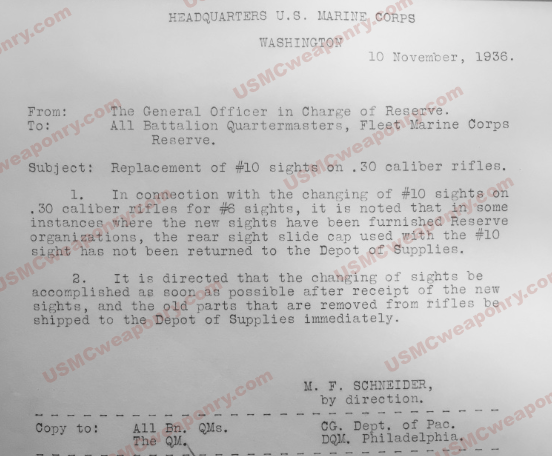

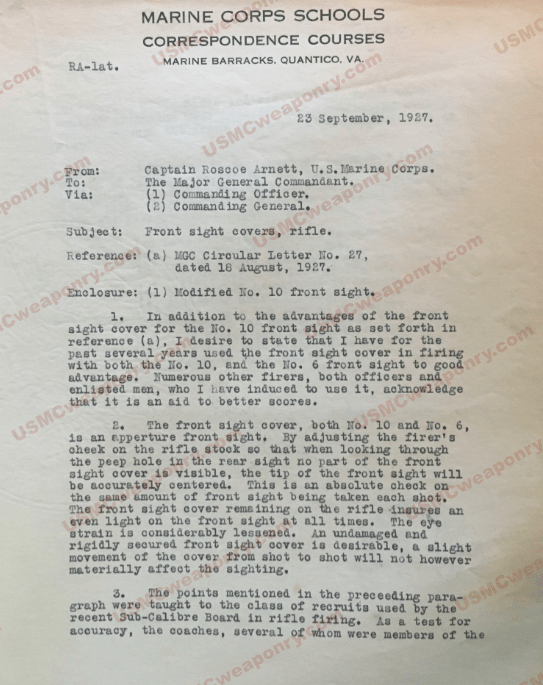

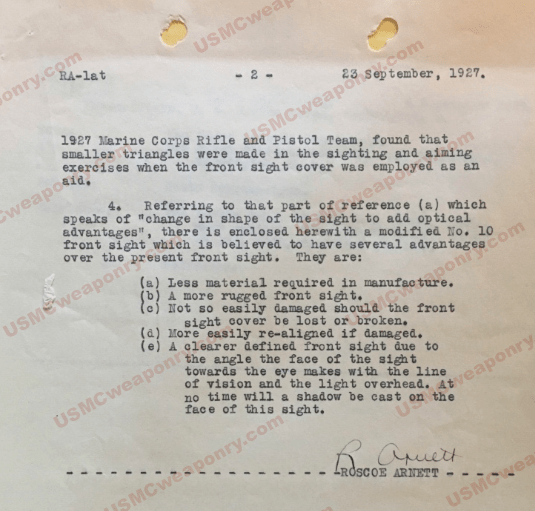

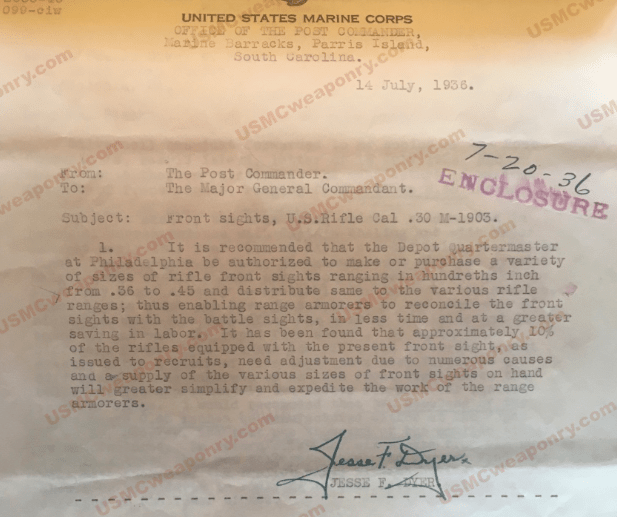

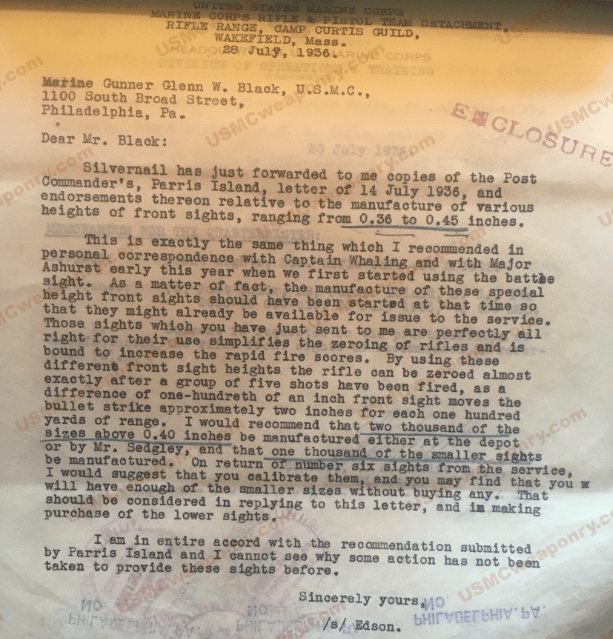

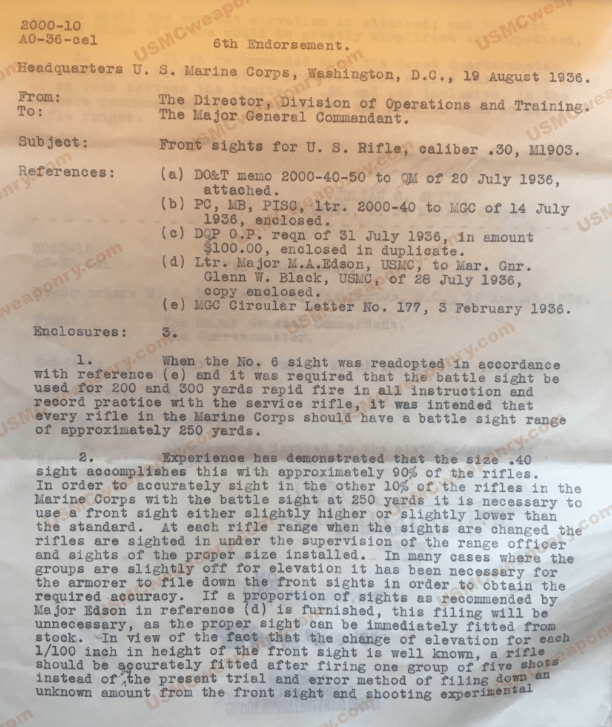

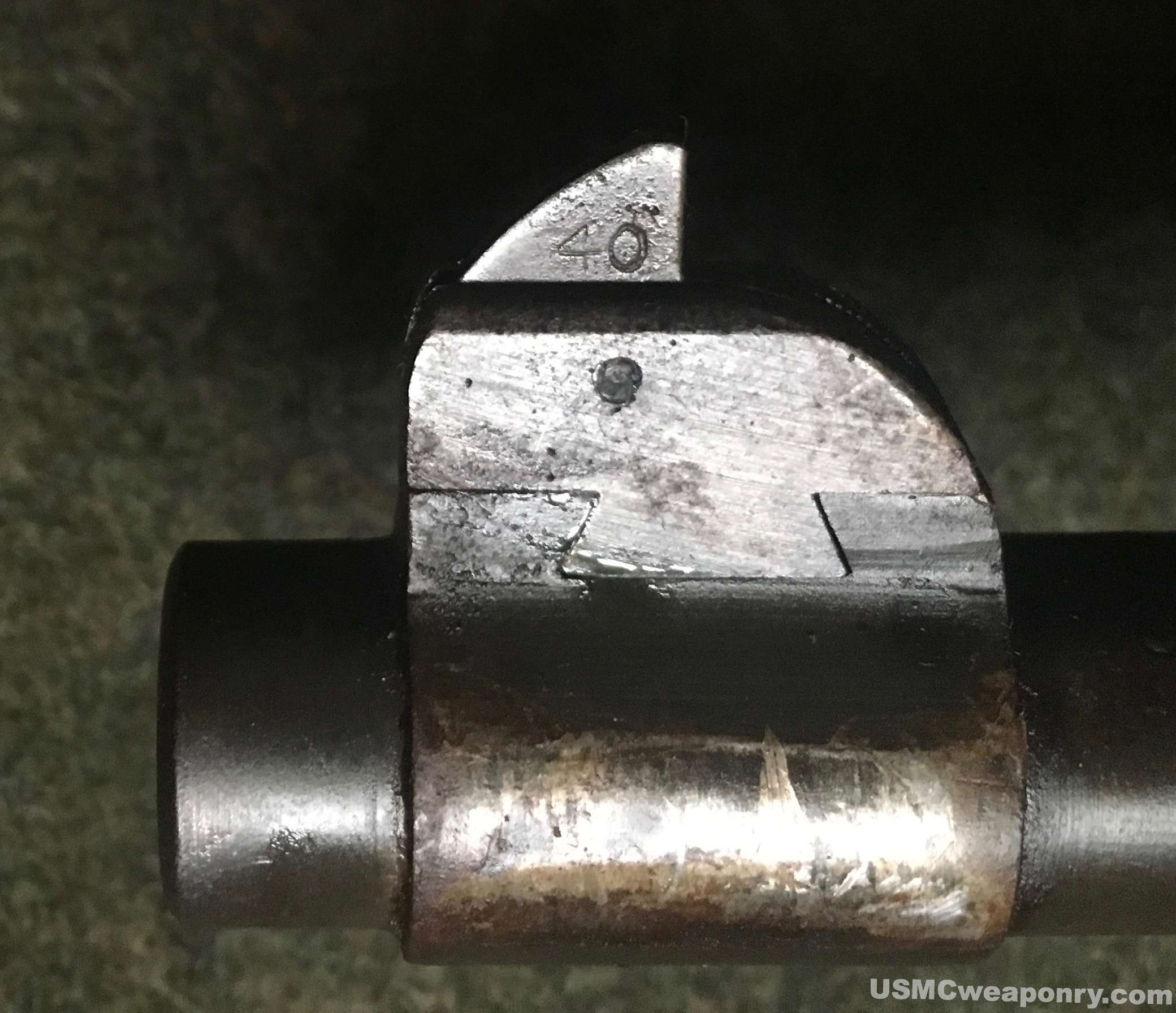

The #10 sight system was great in the field, but came at the cost of accuracy. Marine Corps Rifle Team Captain Merritt Edson had long advocated for the #10s to be replaced, expertise that finally took hold in 1935. That summer, the Marine Corps would begin exchanging the #10 sights for a new, individualized system. The new sights would use the standard #6 front sight’s width, but have a variable height dictated by the zeroing needs of each rifle. While the M1903 was famously accurate, its sights had dogged it from the beginning. Small variances in the rear sight collar, rear sight assembly, and the damage prone front sight led to the need to “custom fit” the front sight blade with a file for it to correctly match the rear sight leaf’s elevation values. This, coupled with the service-wide change in ammunition from the 150 grain 1906 to the 172 grain M1 prompted the Marines to act on Edson’s recommendations. To compensate all issues, the variable height front sight blade was implemented. The front sights would range in height from .35 to .45 and would be used accordingly per rifle to obtain a perfect 600 yard zero on the rear sight leaf. The numbered sight production contract would be awarded to RF Sedgley, a Philadelphia gunsmithing and sales company that had a long relationship with the Marine Corps. Throughout the the rest of the 1930s and into the first years of WWII, all USMC M1903s would be equipped with this new sight system.

Documents detailing the acquisition and employment of the new numbered sight system (NARA).

Examples of USMC numbered front sight blades (Plowman collection).

To avoid damage to the always vulnerable front sight blade, the use of front sight covers was emphasized. Both the standard #6 sight and larger #10 sight covers would be used, and can be observed in WWII-era photographs. The removal of sight covers would be restricted to armorers to minimize the significant number of otherwise serviceable rifles being turned in for overhaul due to loose or damaged front sight blades. As anyone who has attempted to remove an M1903’s sight cover knows, the task can be quite difficult due to the tight fit. Individual Marines had been observed utilizing all sorts of different “methods” to achieve removal, and the subsequent damage to front sight blades was severe enough for orders to be issued mandating sight covers kept on rifles at all times.

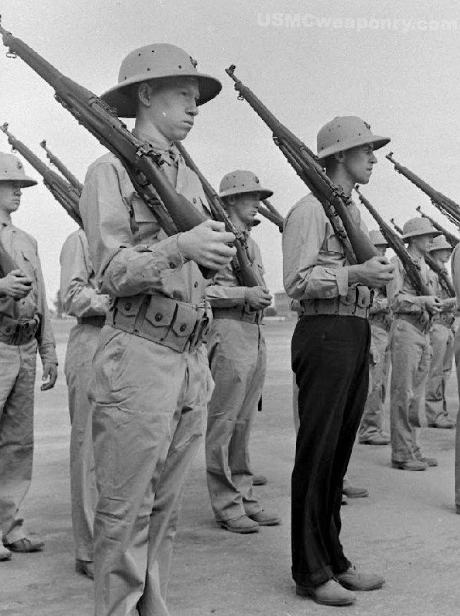

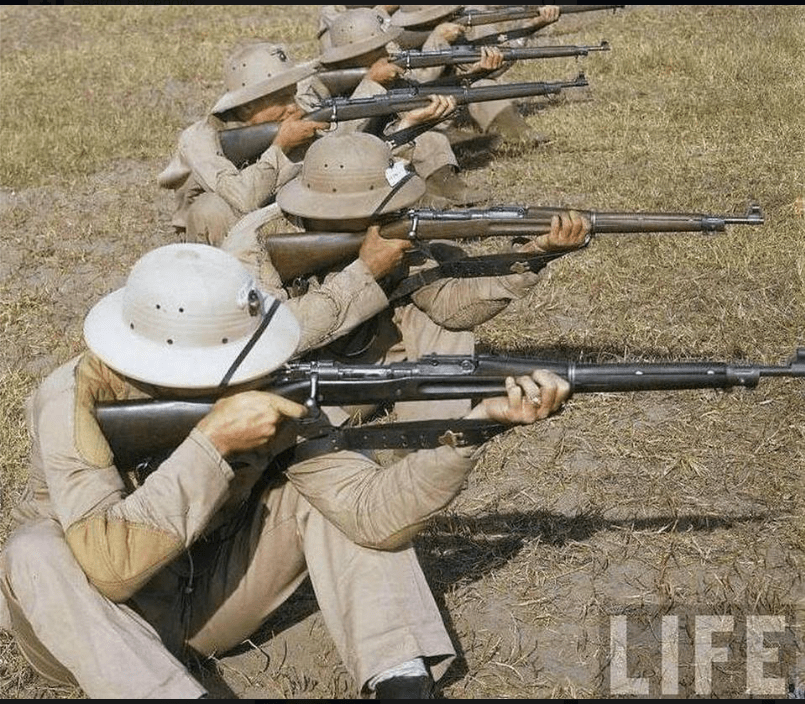

Marines in training prior to WWII, small #6 sight blades can be scene underneath the large #10 sight covers (photos: USMC).

While checkered buttplates where the preference, the Marines would resort to stippling when they were not available (Plowman collection).

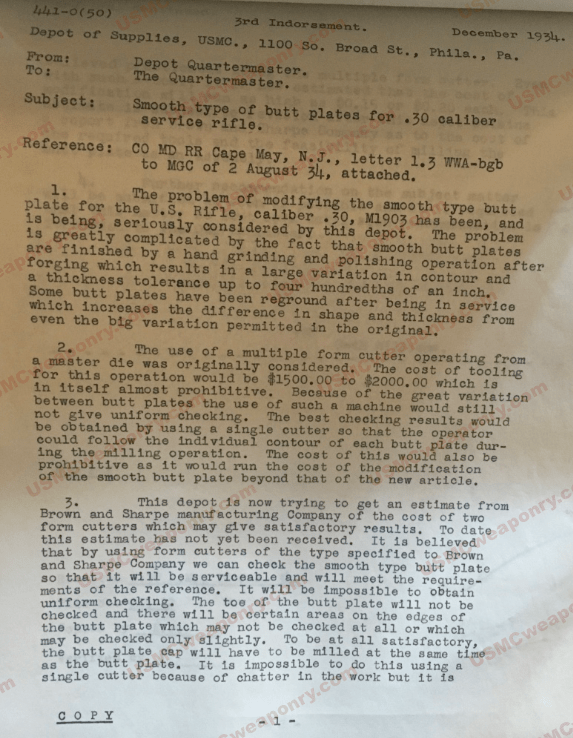

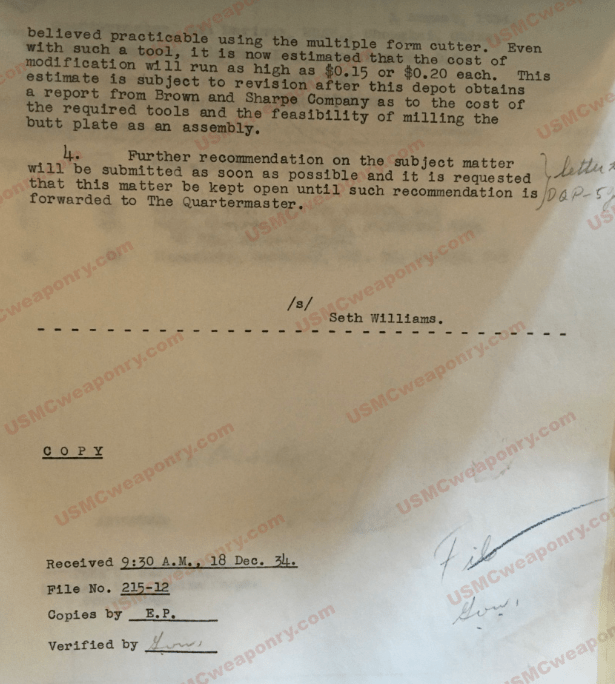

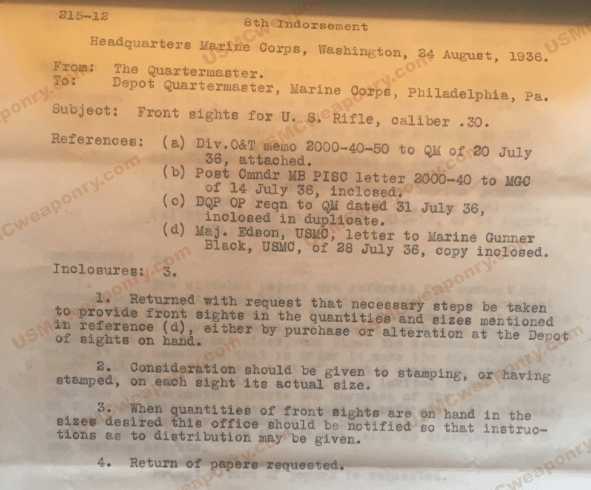

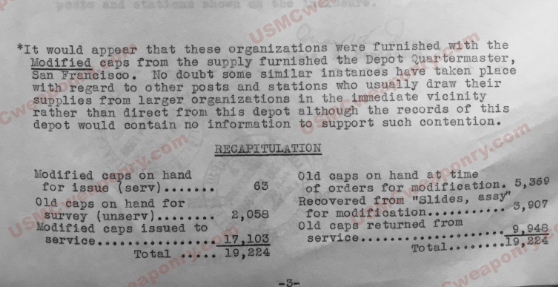

Another change to come about in the mid-30s would be prioritizing the use of checkered buttplates. Springfield Armory and Rock Island Arsenal had begun producing checkered buttplates in 1910, just as the Marine Corps was in the process of outfitting with the M1903. World War I mass production demands the lead to the Ordnance Department discontinuing the checkering process, but it would resume in 1920 until the end of production. The advantage of the checkered design was a coarse surface that could be firmly secured in the shoulder, as smooth buttplates were prone to slip. The Marines decided that their active duty forces should make a priority of utilizing these buttplates, and that the Depot of Supplies in Philadelphia should use them whenever possible. At the time, the Marines had roughly 55,000 M1903s service wide with just over 14,000 in use, the rest were in storage as war reserve. This disparity would make it possible for preferred items like checkered buttplates to be cherrypicked for active duty rifles.

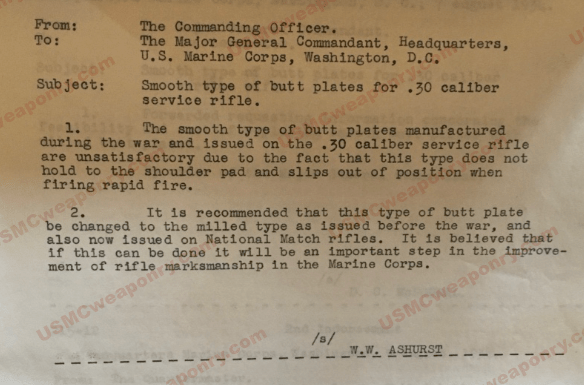

Eventually, the Marine Corps began exploring options to modify the tens of thousands of smooth buttplates that resided on the majority of their rifles. Marine ordnance officers began corresponding with Springfield Armory as to how checkered buttplates were produced. As they would find out, the price of obtaining the master die operated multiple form cutter machine was “itself almost prohibitive,” according to Marine ordnance officer Colonel Seth Williams. The Brown & Sharpe company was consulted as to whether they could furnish the Marines with form cutters which would have provided a rough and nonuniform, albeit satisfactory result. This option appears to have been scrapped, as no contract with Brown & Sharpe is recorded. With no further mention of any attempt to checker smooth buttplates through machine milling, an unofficial solution appears to have taken place. USMC rebuilt M1903s are often noticed with “stippling” on their smooth buttplates. While the practice is not dictated in existing archival documentation, it is logical that it began not long after machining inquiries concluded. It is also worth pointing out that the type of buttplate a Marine rifle has can be a clue to rebuild date. Mid to late 1930s rebuilds are more often seen with checkered buttplates, while WWII rebuilds are more likely to have stippling. This is far from a rule though, and either are found on USMC M1903s from this era. Not all smooth buttplates would have been stippled either, and the presence of a smooth buttplate on a USMC M1903 is does not mean it is not original to Marine Corps rebuild.

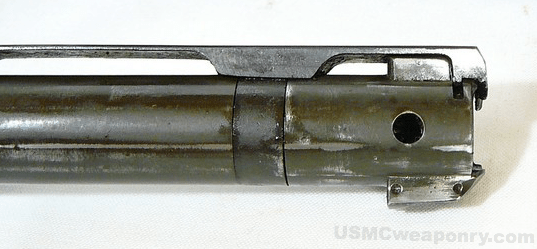

Example of colloquially termed “vise marks” on a WWII USMC M1903 rebuild (Norton collection).

At some point during the 1930s overhauls, Marine armorers began the practice of using a plumber’s wrench (or plumber’s table) to quickly and firmly grip a barrel during replacement. The teeth on the plumber’s equipment would bite into the barrel during the removal and installation process, thus leaving behind the iconic “vise marks” on the barrel’s base. Rudimentary but speedy, the plumber’s equipment would be an alternative to the traditional vise and insert blocks, which are specially made to fit the barrel. As any gunsmith will tell, these are prone to slippage and and can make a barrel change a frustrating, time consuming project. It is unknown if ease of operation was the motivation behind the Marine Corps’ decision to use plumber’s equipment, and as of yet no archival information has been found on the matter. It is also possible this practice only occurred at one rebuild facility, as not all replacement barrels have these marks. It does appear to have occurred most heavily in the late 1930s to the early 1940s, which is logical as this was the height of the Marine Corps’ WWII M1903 rebuild program.

Documents detailing the search for tooling to checker buttplates, the #10 sight replacement process, and the Marine rifle team using tall #10 sight covers with their National Match #6 sights during competition. Also included is the discussion on “modified” rear sight caps, which as of yet is a modification that has not been completely identified (NARA).

In 1938, a survey was taken of the relatively sizable amount of M1903s held in war reserve at the Depot of Supplies in Philadelphia. The amount of high number or low number receivers on the rifles was more or less split down the middle, and about a quarter had unserviceable barrels. Many new barrels were ordered from Springfield Armory to begin the overhaul process with a goal of establishing an effective war reserve of rifles to draw form during the next World War. Due to this barrels from the first half of 1938, particularly those produced in March, April, and May are often seen on USMC M1903s. While low numbered receivers were deemed appropriate for firing regular ammunition in the late 1920s, many infantrymen had their rifles exchanged for high number variants to allow for safe rifle grenade firing. The Marines had a relatively small force in the years to follow, allowing most of the operational forces to be issued high number rifles for grenade employment flexibility. In 1937 a directive was issued calling for the removal of low numbered receivers from service. With just a quarter of the Marine Corps’ war reserve of M1903s having serviceable barrels with high numbered receivers, decisions and prompt action were needed to build a sufficient war reserve. With the rise of the Japanese Empire in the Pacific and Hitler in Europe, war was on the horizon and Marine Headquarters was ware of the potential for a rapid mobilization. These threats meant low number receivers would have to be used after all, and the testing and modification that followed would leave many USMC M1903s with their most known feature: the “Hatcher Hole.”

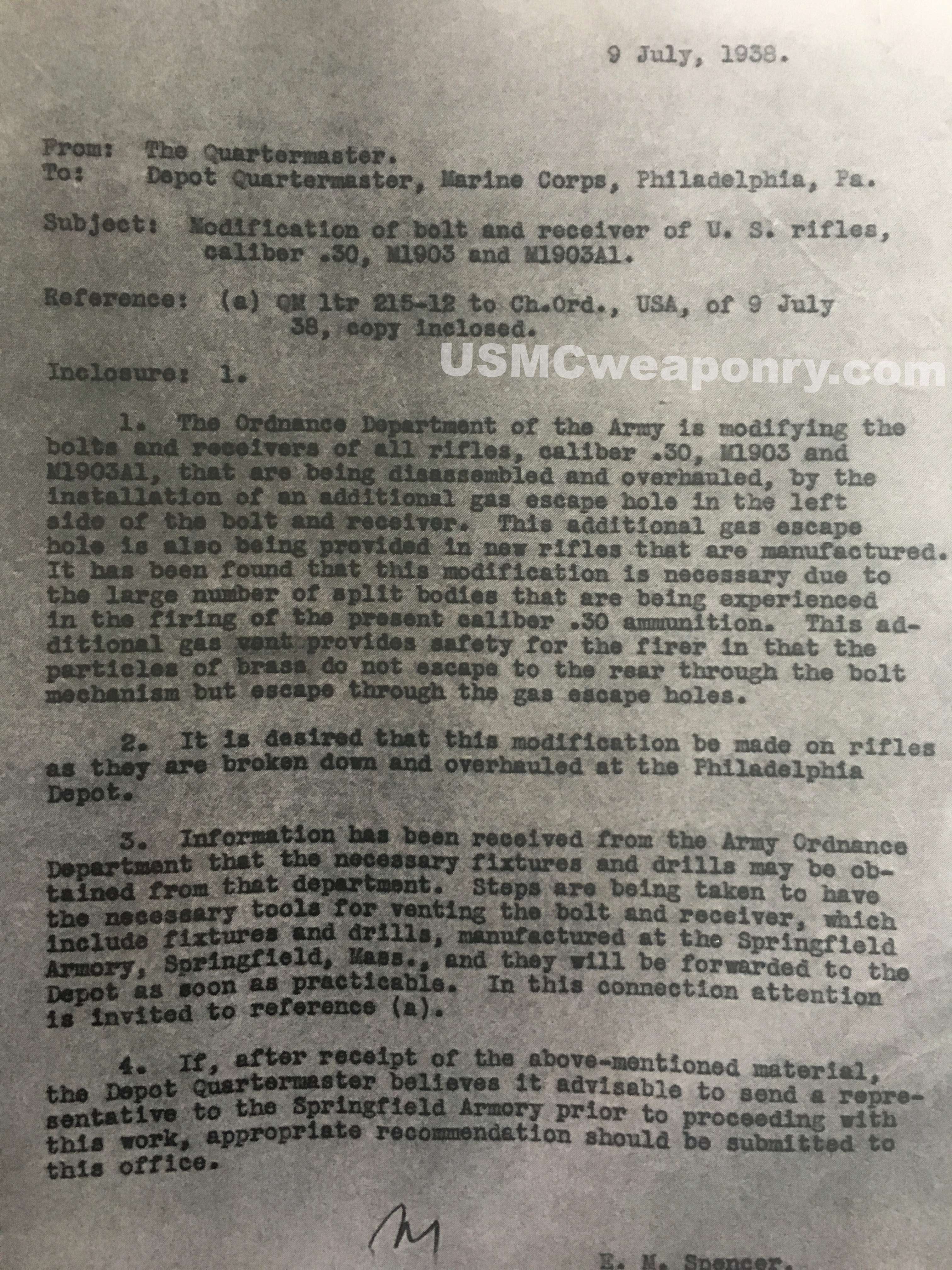

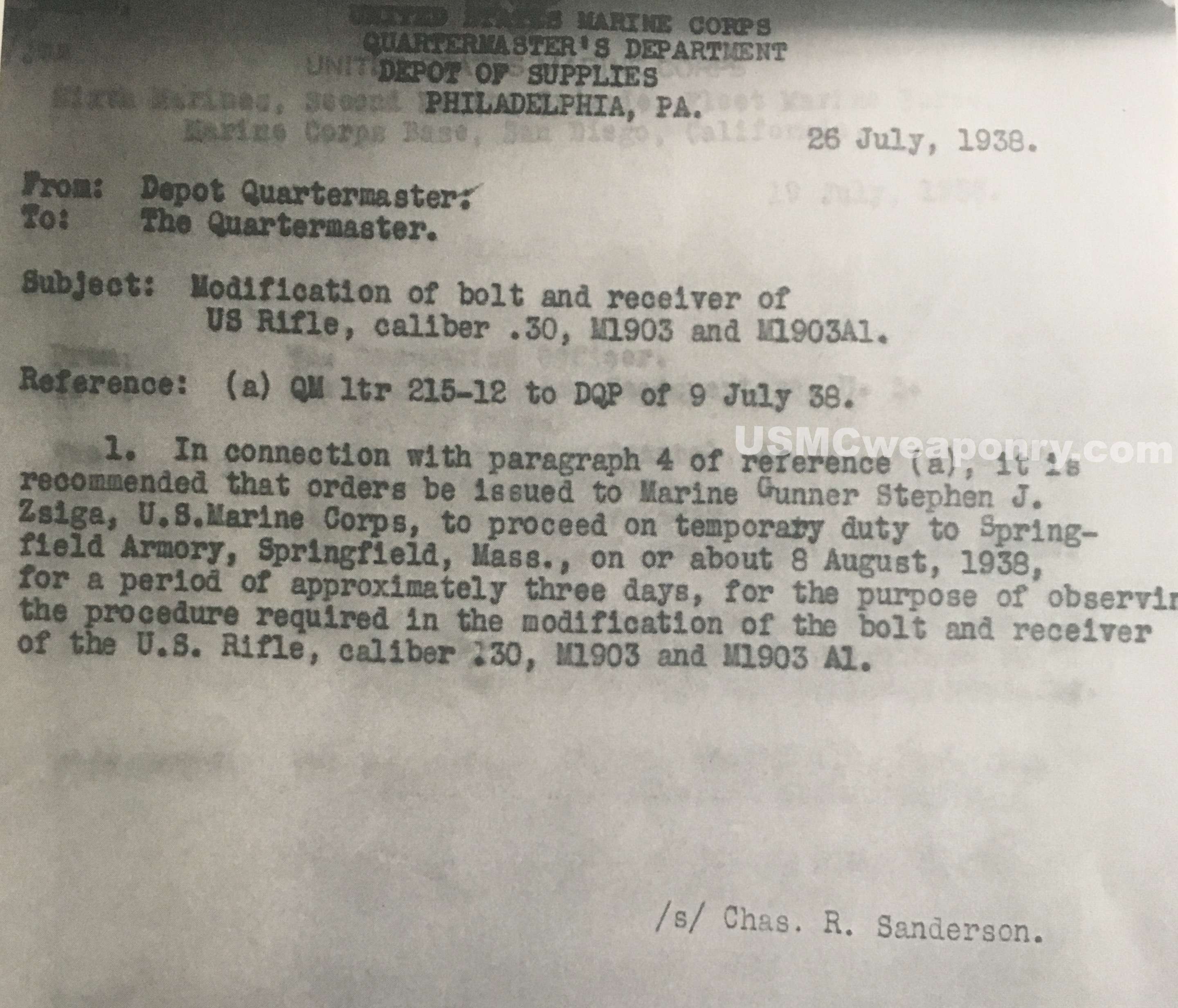

The Marines adopted the idea of the “Hatcher Hole” from the army, and sent Marine Gunner Steven J. Zsiga to Springfield Armory to observe the procedure (NARA).

Springfield Armory began drilling emergency ventilation holes on the left side of M1903 bolts and receivers in the mid 1930s. The rationale was that during a catastrophic malfunction an extra gas escape hole would allow for brass particles to exit out the side instead of the rear, protecting the rifleman. Later dubbed the “Hatcher Hole” after army ordnance officer Julian Hatcher, the Marine Corps decided this was a solution to the low number receiver problem. In 1938, Marine Corps Headquarters would order Hatcher Holes to be added to all rifles undergoing major overhaul regardless of serial number. The army, though the parent of the Hatcher Hole, appears to have used it very sparingly according to photographic evidence and official documentation. The main reason for this was M1903s were on the army’s back-burner in late 1930s as the service was transitioning to the new semiautomatic M1 Garand. Springfield Armory was being tooled up for mass production, and by the time the Second World War was inevitable many of the army’s infantry units were fully equipped with M1s. Being pessimistic towards the M1 Garand, the Marine Corps moved ahead with the modification of M1903 receivers. By the American entrance into World War II, a significant amount of USMC M1903s had been modified with Hatcher Holes.

Example of a “Hatcher Hole” on a USMC M1903. As in the case of this rifle, most Marine drilled Hatcher Holes leave a slight lip on the outside and can appear crude. To the right is an enlarged bolt gas escape hole from Marine rebuild. In tandem, the added emergency venting was designed to give an extra layer of safety (Norton collection).

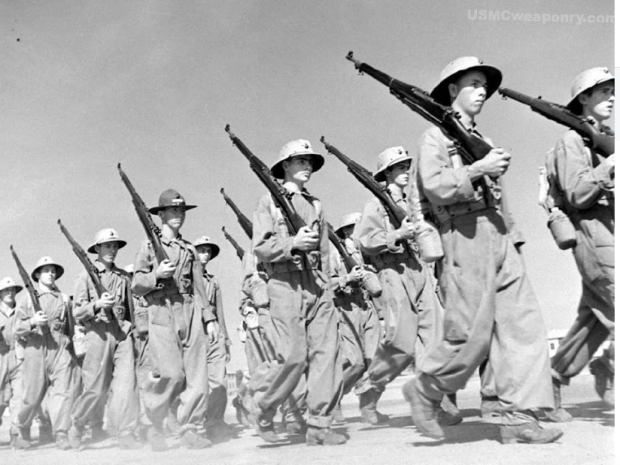

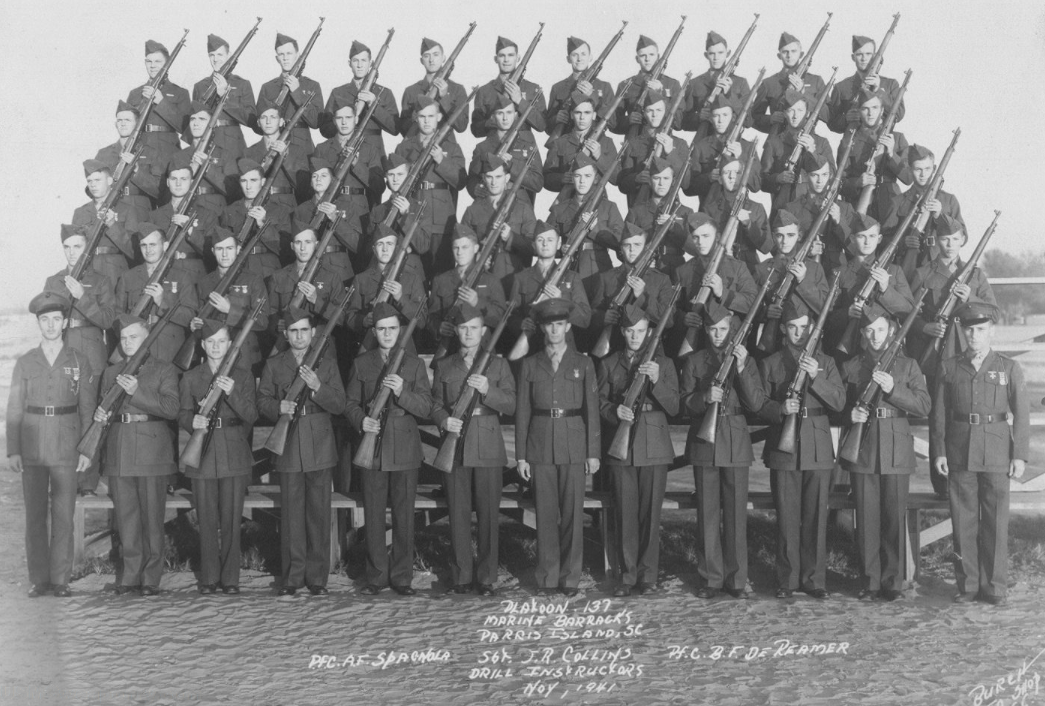

Mix of rifles with and without Hatcher Holes in the hands of new Marines, early 1942 (photos: USMC).

Examples of 1930s USMC rebuilt M1903s. The top rifle saw major overhaul after 1938, as evident by the Hatcher Hole. Both are similar in that they have numbered front sights, finely checkered buttplates, and notches for bolt handle clearance cut into their stocks. The top rifle has a recycled SA 8-11 barrel, while the bottom rifle has an SA 3-32, a post Banana Wars rebuild. The finish and appearance of either are what the vast majority of M1903s on Guadalcanal would have resembled (Plowman collection).

USMC Rock Island Arsenal M1903 displaying a darker grey finish from the manganese parkerizing solution that was commonplace prior to WWII. During the war the Marine Corps would switch to a zinc phosphate solution that left a much lighter finish (Plowman collection).

In addition to the Hatcher Hole the Marine Corps would also perform a Rockwell hardness test on M1903 receivers during major overhaul. Surprisingly, testing showed that high numbered receivers were just as likely to shatter under severe pressure. In 1938 all rifles sent to Philadelphia Depot would have their receivers tested, with those that scored between 20 and 45 being considered acceptable. The test would leave a “punch mark” in front of the serial number of each receiver. Receivers that failed the test were not destroyed, but were “drawn back” until a successful result was achieved. Although it isn’t mentioned specifically in documentation, the practice of having receivers put through the Rockwell test appears to have been brief. While many WWII era USMC M1903s exist, the presence of a punch mark is somewhat rare. Most likely, the chaos of wartime mobilization made the time to perform the test impractical.

A modification informally brought to the Fleet Marine Force by way of the Marine Corps Rifle Team, a small notch would be carved into the stocks of M1903s to aid in the clearance of the bolt handle, as seen on the rifle above (photo: USMC).

Documented USMC M1903 with punch mark in front of the serial number from the Rockwell hardness test. This particular rifle was one of 34 from the Marine 2nd Anti-Aircraft Artillery Battalion stationed in San Diego that surveyed as needing overhaul in early 1938. The bolt is serialized to the receiver, another practice that began in 1938. This rifle was overhauled at least once more after 1938, as it has a Sedgley USMC 9-42 barrel (Norton collection).

Documented to the 4th Marine Regiment in 1926, Springfield Armory USMC M1903 #1024684 has a Rockwell hardness test punch mark, but it did not receive the Hatcher Hole modification as it wasn’t in need of major overhaul at the time (Niederman collection).

Late 1930s rebuild USMC M1903 issued to Private Alphonzo Land. Private Land served in various companies of the 5th Marines in Nicaragua before being transferred to stateside duties. Although serial numbers overlap and Marine documentation rarely differentiates between SA and RIA production, a serial number “hit” coupled with USMC rebuild traits make it virtually certain as to which manufacture a documented USMC M1903 was. (NARA / Kalman collection).

For most of the interwar years, the Marine ordnance facility in San Francisco and lower echelon armorers Corps-wide had performed M1903 overhauls. This frustrated Marine armorers at the Philadelphia Depot, as the work being performed elsewhere was done so at a lower standard. On top of this, rifles were being cannibalized at the unit level to keep others serviceable and then sent to Philadelphia in pieces. Unit level bolts were commonly swapped, leaving a fair amount of rifles with dangerous headspacing. In some organizations, like Marine Reserve units, rifle bolts were collected after weekend drill and stored in a locked box. During the next drill, bolts were passed out at random, creating a dangerous “Russian roulette” headspace situation. To fix this, Marine gunners were ordered to inspect reserve M1903s rifle by rifle, making sure each had a bolt that headspaced safely. Next, the safely matching bolts would be serialized by an electropencil, ensuring each Marine would receive the correct bolt for their rifle every drill.

On the active duty side, a policy was adopted that only Philadelphia Depot armorers were allowed to set headspacing. Bolts would be serialized like they were for reserve units and ordered to remain in their matching rifle until subsequent overhaul. As the Marine Corps continued to build up a war reserve of M1903s, significant amount of new bolts were ordered. The Marines would specifically request blued B2 replacement bolts from Springfield Armory. Improved heat treatment coupled with penetrate blued finish made B2 bolts cycle more smoothly, giving them a longer service life. The Marines specifically requested large quantities of B2 bolts from Springfield Armory prior to WWII. Penetrate blued instead of parkerized, B2 bolts offered precise headspacing and smoother function (Plowman collection).

The Marines specifically requested large quantities of B2 bolts from Springfield Armory prior to WWII. Penetrate blued instead of parkerized, B2 bolts offered precise headspacing and smoother function (Plowman collection).

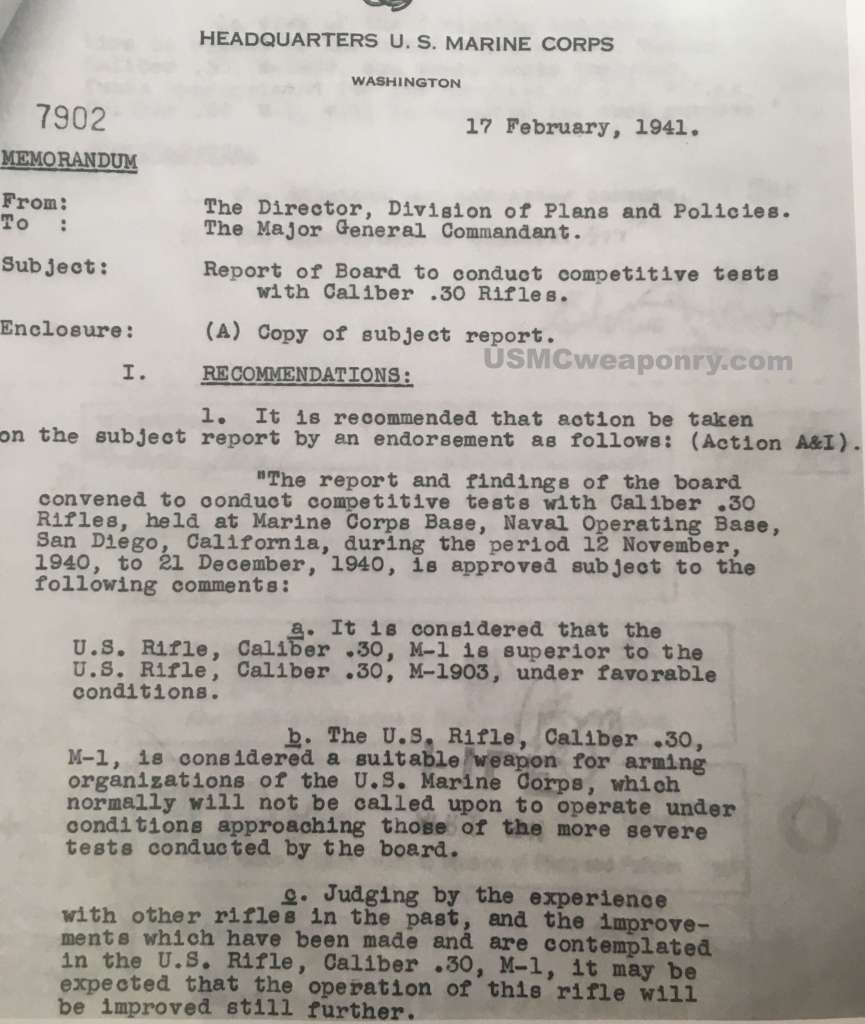

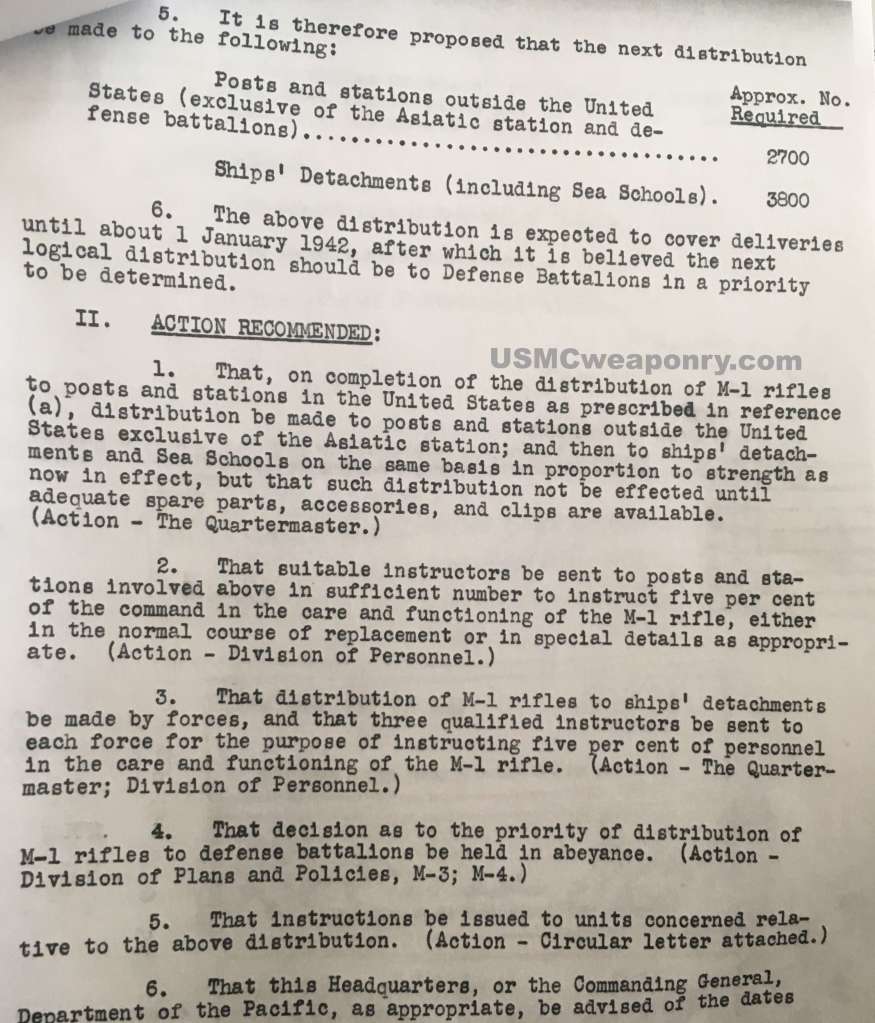

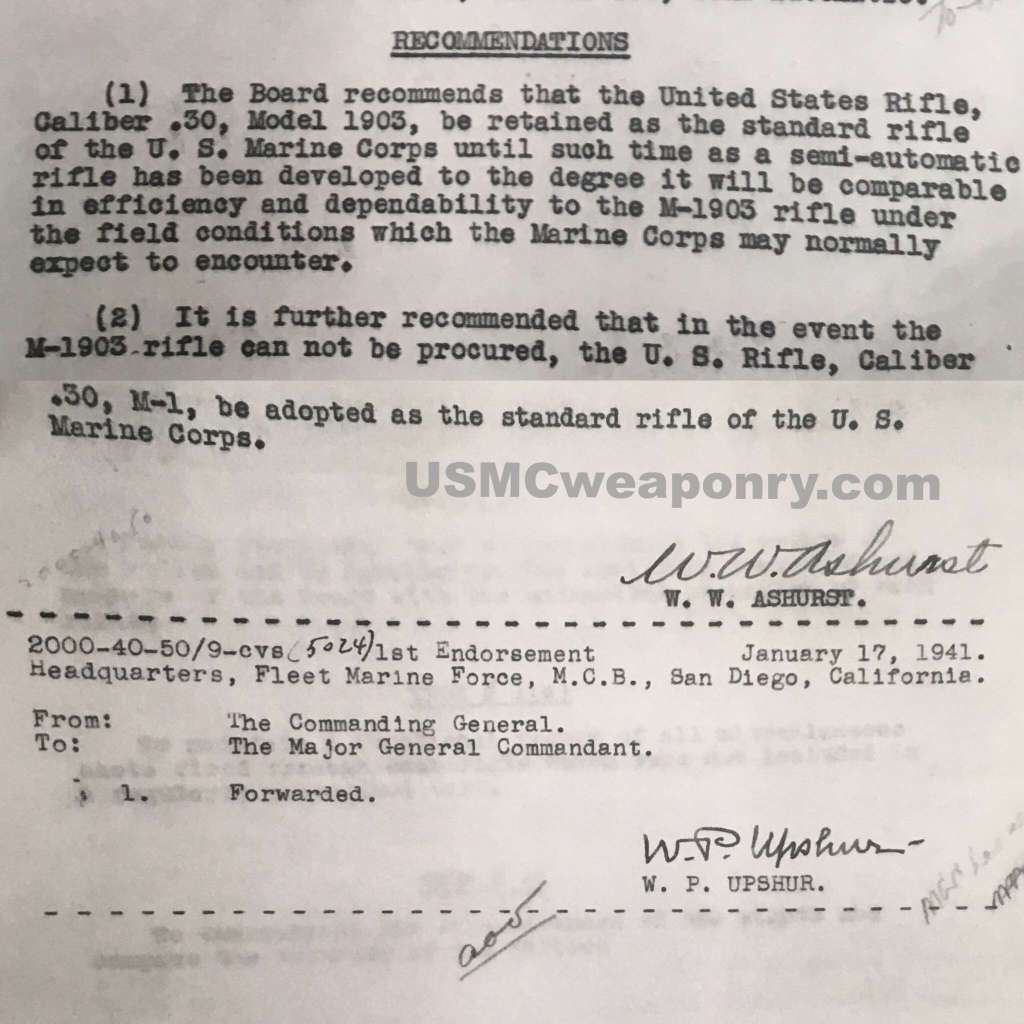

As the Marine Corps entered the 1940s, the rest of the world was already at war. Keeping the growing force equipped with rifles had finally reached a crisis point. The army’s adoption of the M1 Garand meant production of the M1903 had ceased. The Marines tested the M1 Garand at length, beginning with 400 very early “gas trap” models – which were considered needing of improvement. Later M1 Garands with the upgraded gas cylinder design were also tested, but the Marine Corps being ever cautious decided that while the M1 Garand would become their standard service rifle, the M1903 would continue to be the battle rifle of the Marine Divisions. The Marine Divisions were the home of the seasoned active duty infantry regiments of the Fleet Marine Force, and the thought at the time was the M1 was too unproven in the sand and salt of amphibious warfare. What wasn’t disputed was that the M1 held a significant advantage in firepower, and was a superior weapon for static defense, guard duty, and in favorable conditions. As such, the earliest M1s procured would go to non frontline units. In the opinion of Marine Headquarters, this would give Springfield Armory proper time to fine tune the M1, at which point the Marine Divisions would trade in their M1903s for the new rifle.

M1 Garand testing documents. The Marine Corps would officially adopt the M1 Garand in 1941, but keep the infantrymen of the Marine Divisions armed with the M1903 until the M1 was further refined (NARA).

As 1941 progressed, the Marine Corps contracted Remington to supply small parts for their M1903 rebuilds. Remington had “tooled up” with the old M1903 equipment from Rock Island Arsenal, and would go into production of new M1903s and small parts in late 1941. The Marines were eager to get their hands on the new Remington M1903s, but production was primarily allocated to the British as part of the Lend-Lease program. What production was to go to the US military was promised to the Navy, leaving the Marines with the small parts order and no rifles. Many WWII rebuild USMC M1903s can be observed with Remington made items, most commonly bolts and their parts, triggers, magazine cutoffs, rear sights, and various springs. Multiple contracts were also made with RF Sedgley for barrels. Sedgley barrels were marked “U.S.M.C.” above the date and have become very desirable to collectors, not to mention one of the exceedingly rare occasions where a USMC marking is genuine and actually an abbreviation for the United States Marine Corps.

Marine paratroopers with M1903 rifles during a training event (photo: USMC)

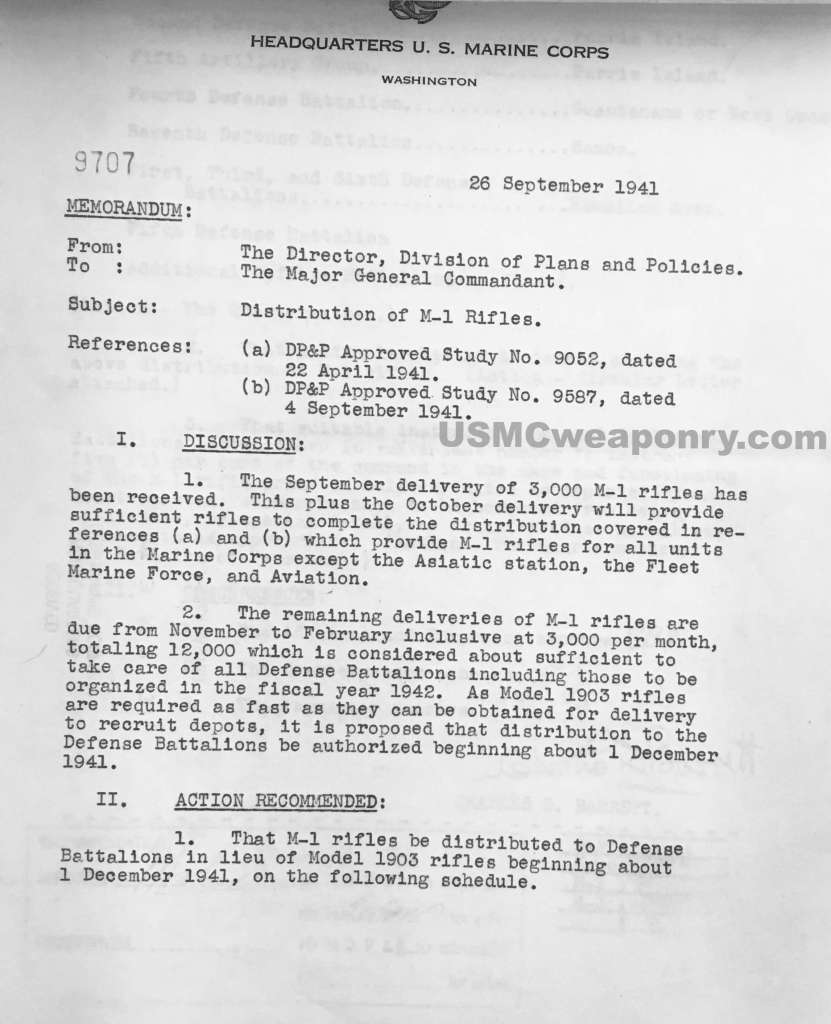

Marine recruits at the Parris Island rifle range in 1941 (photo: Life magazine).

The next M1903 rebuild issue to address was the procurement of new stocks. Prior to the outbreak of WWII, the Marines had refused pistol gripped C stocks to allow for a uniformity in the training of Marine recruits, but this was scrapped after the attacks at Pearl Harbor. While some small orders for straight stocks had been filled Springfield Armory and other contractors, the American entry into World War II led to the Marines decided to take anything they could get. C stocks, Pederson Device cut Mark 1 stocks, and even unserviceable stocks were drained from any army arsenal nearby. Marine armorers in Philadelphia hastily mounted barreled actions to these new stocks to supply the swelling ranks of rcruits at San Diego and Parris Island. Standard Marine M1903 service rifles with C stocks can be seen in the hands of recruits in the immediate days following Pearl Harbor, and in combat photos from Guadalcanal.

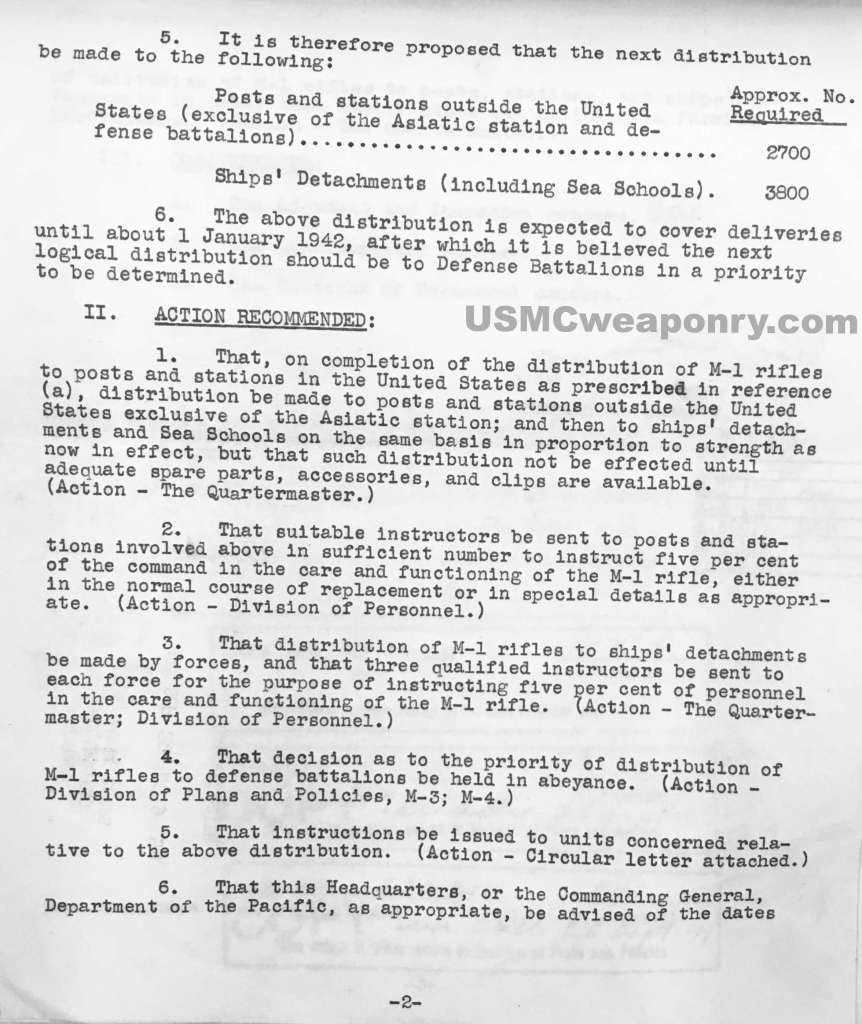

Marine recruits march to the range with a mix of rifles, including one with a newly accepted pistol gripped C stock (USMC).

The Marine Corps scrambled for a solution to get their hands on more M1903s in early 1942. While the Marine Corps Rifle Team had received roughly 150 National Match rifles annually, no as-new service rifles had been procured since the late 1920s. The only rifles that could be spared were 33,000 M1903s from the Navy that had been used for training sailors at their Great Lakes Training Center. The majority of these rifles needed major overhaul, but the Marines took them regardless. It is unlikely that many made it into the hands the 1st and 2nd Marine Divisions before they departed for the South Pacific, but a few of the better conditioned ones may have. The difference in traits between Navy and Marine M1903s is still somewhat of a question mark, as Navy rebuilds have not been thoroughly studied. This acquisition from the Navy also opens the door for the possibility that the Marines did receive some Remington M1903s, though this has never been proven. What is certain though is a wide range of M1903s were in the hands of early WWII Marines.

(Left): USMC contract barrel produced by RF Sedgley, as evident by their Circled S logo. (Right): WWII era USMC M1903 with a trigger, sear, and magazine cutoff marked R indicating Remington production.

Left: a mix of M1903s and M1 Garands in a November, 1941 photo from recruit training at Parris Island, S.C. The recruits armed with M1903s would be heading to the Marine Divisions. Right: Marines watching for Japanese aircraft on December 7th, 1941 (USMC).

Left: The 1st Defense Battalion, who would defend Wake Island against waves of Japanese amphibious assaults before finally being overrun. Marine defense battalions were in the process of being armed with M1 Garands in very early 1942, but the logistical situation in the South Pacific precluded their making it to Wake in time. Right: The men of the 4th Marine Regiment pack equipment towards the defensive positions they would mount at Corregidor in early 1942 (NARA/USMC).

USMC M1903 documented to the 4th Marine Division in 1926. The 4th Marines would engage the invading Japanese at Corregidor during the ill-fated Bataan Defense.

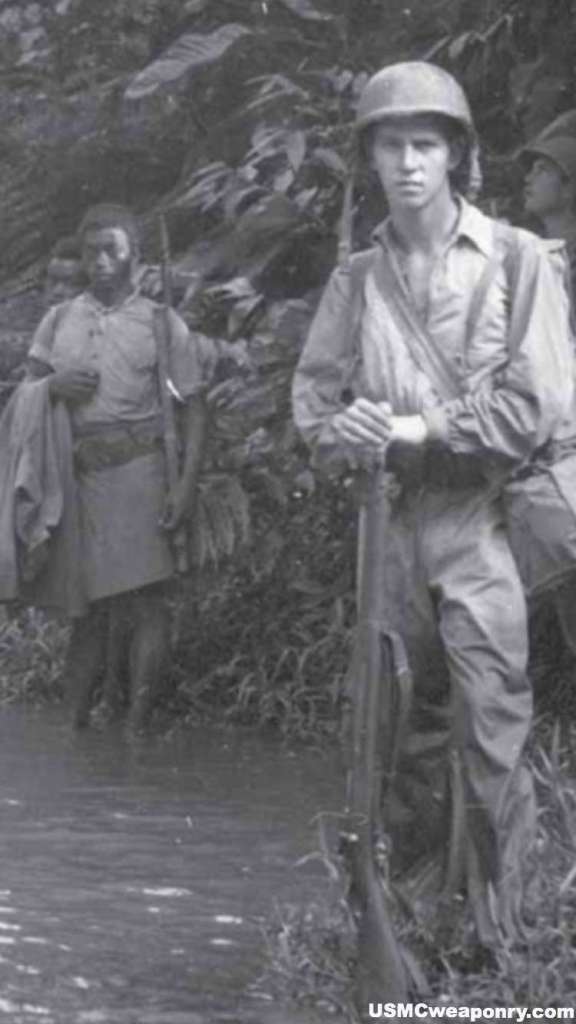

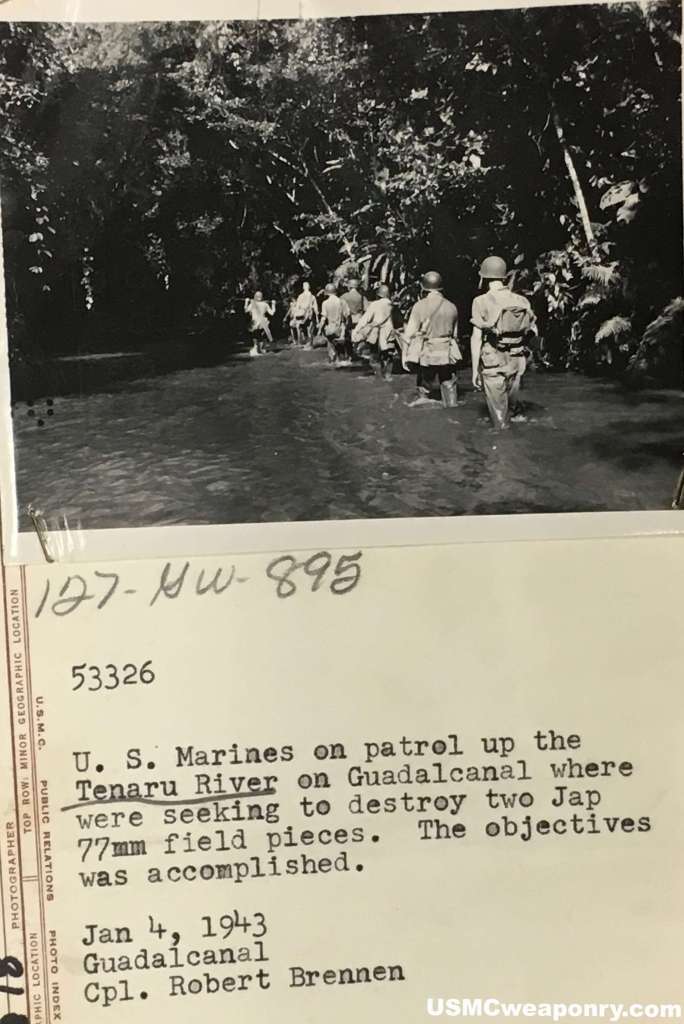

The tremendous defenses mounted on Wake Island and Corregidor were a furious re-acclimations to combat for the Marine Corps and their venerable Springfield rifles. The controversial refusal to reinforce the defenders and their subsequent capture left a Marine Corps eager for the chance to earn America it’s first major victory by land. That chance would come on an obscure tropical island named Guadalcanal. While some of the men of the 3rd Defense Battalion and artillerymen in the 11th Marine Regiment were armed with M1 Garands, the vast majority of the 1st Marine Division came ashore with M1903s when they landed on August 7th, 1942. A world war prior, M1903 equipped Marine riflemen had earned a deadly reputation for successfully engaging German soldiers at Belleau Wood from 800 yards out. On Guadalcanal, the engagements would seldom be farther than a couple hundred yards.

Springfield Armory USMC M1903 #840216, brought home from Guadalcanal by H Company, 2d Battalion, 5th Marines Platoon Sergeant Roy Jowers. This particular rifle bears a variety of early/mid 1930’s rebuild traits. It has an SA 3-32 barrel, .40 height numbered front sight, and a checkered buttplate (Plowman collection).

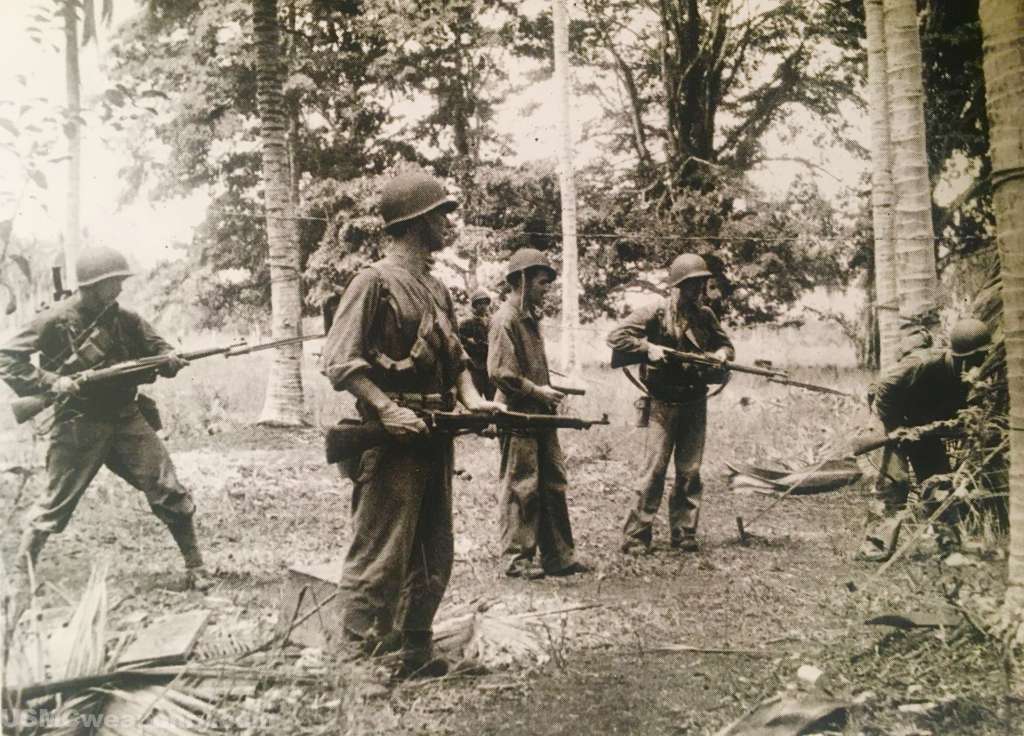

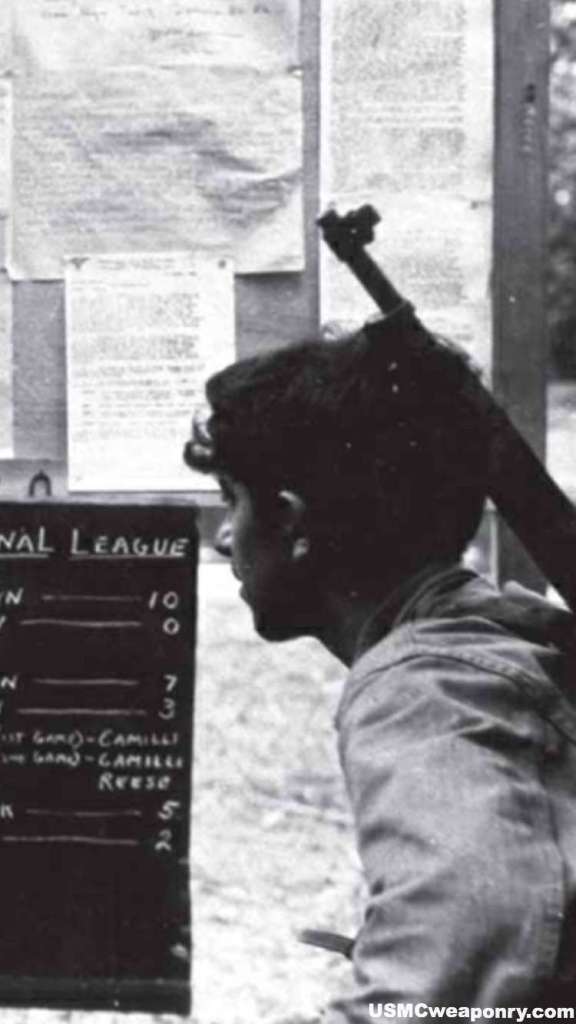

The condition of the USMC M1903s on Guadalcanal would be as varied as the men using them, some would be old and salty with relatively little modifications since their acquisition in the WWI era. Others would be fresh with all of the latest improvements and many parts of new manufacture. With the practice of rifles being issued to an individual Marine for the duration of their career (or until a rifle needed to be turned in for overhaul), the freshly overhauled M1903s were often in the hands of the scores of new Marines that had joined the ranks of 1st Marine Division following Pearl Harbor. Photographs from the campaign display the wide ranging appearance of the M1903s the Marines brought ashore with them, but what is consistent is their exceptional performance in the brutal conflict which saw wave after wave of Japanese attackers repulsed. In desperate fights such as the Battle of the Tenaru, Bloody Ridge, and the Battle of Henderson Field, the 1st Marine Division would hold the line.

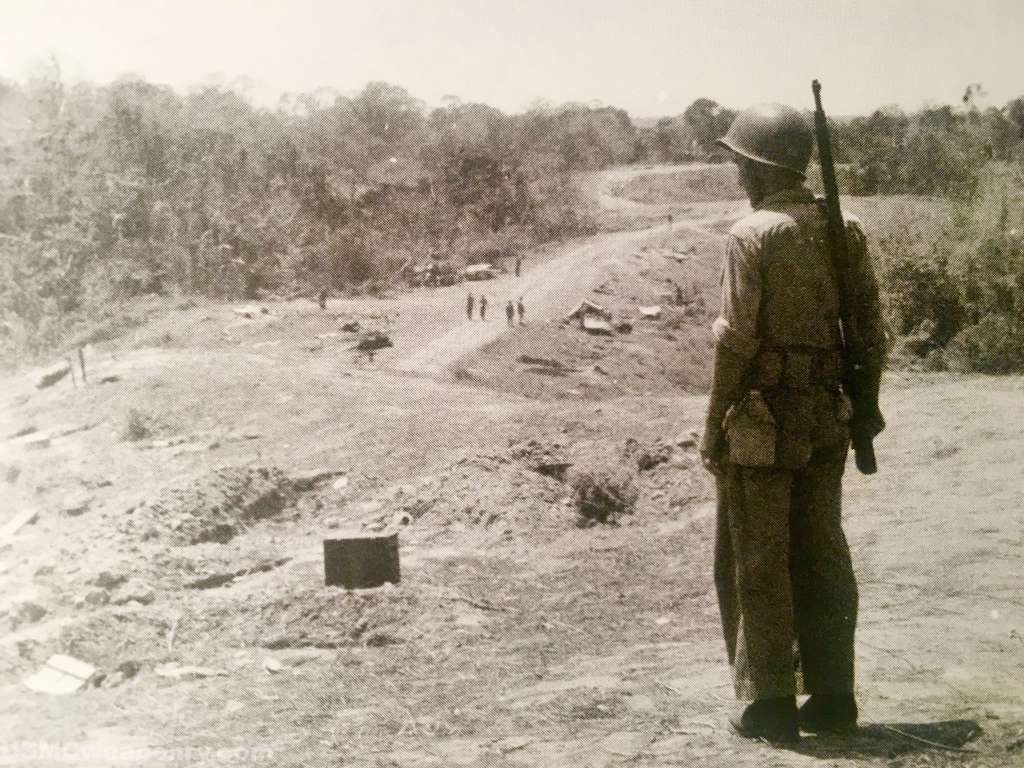

(Top Left): The Marines land on Guadalcanal, August 7th, 1942. (Top Middle): Marines with their M1903s clearing fighting positions.(Top Right): Marines with a captured Japanese soldier, early in the campaign. (Bottom): A Marine overlooks “Bloody Ridge,” where the elite Marines of the 1st Raider Battalion, 1st Marine Parachute Battalion, and 2d Battalion, 5th Marines mounted a tenacious and successful defense on September 12-14th, 1942 (NARA).

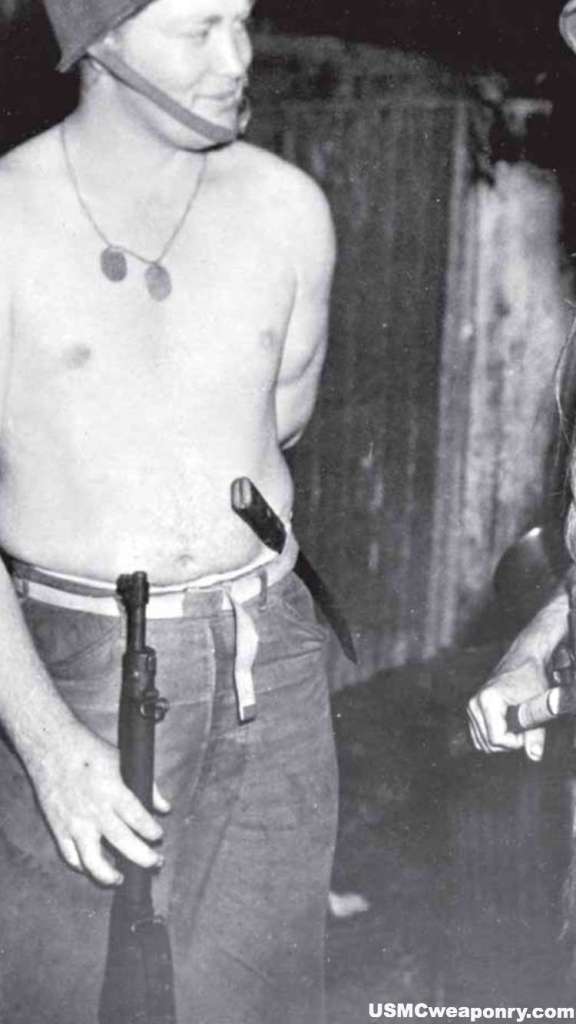

A souvenir savvy Marine with his rifle on Guadalcanal. The high quality of the photo shows this M1903 to be of Springfield Armory manufacture, without a Hatcher Hole, and having a #10 front sight cover (USMC).

USMC Rock Island Arsenal M1903 with “Guadalcanal Is. Solomon Islands, August, 1942” carved into the stock. This particular stock was a pre WWI “high-wood” version with a notch cut into it to expose the Hatcher Hole, and allow it to function if needed. The trigger guard is staked, a common practice by the Marine Corps to prevent the screws from backing out in the field (Duffy collection).

Marines with their M1903s on Guadalcanal (NARA/USMC).

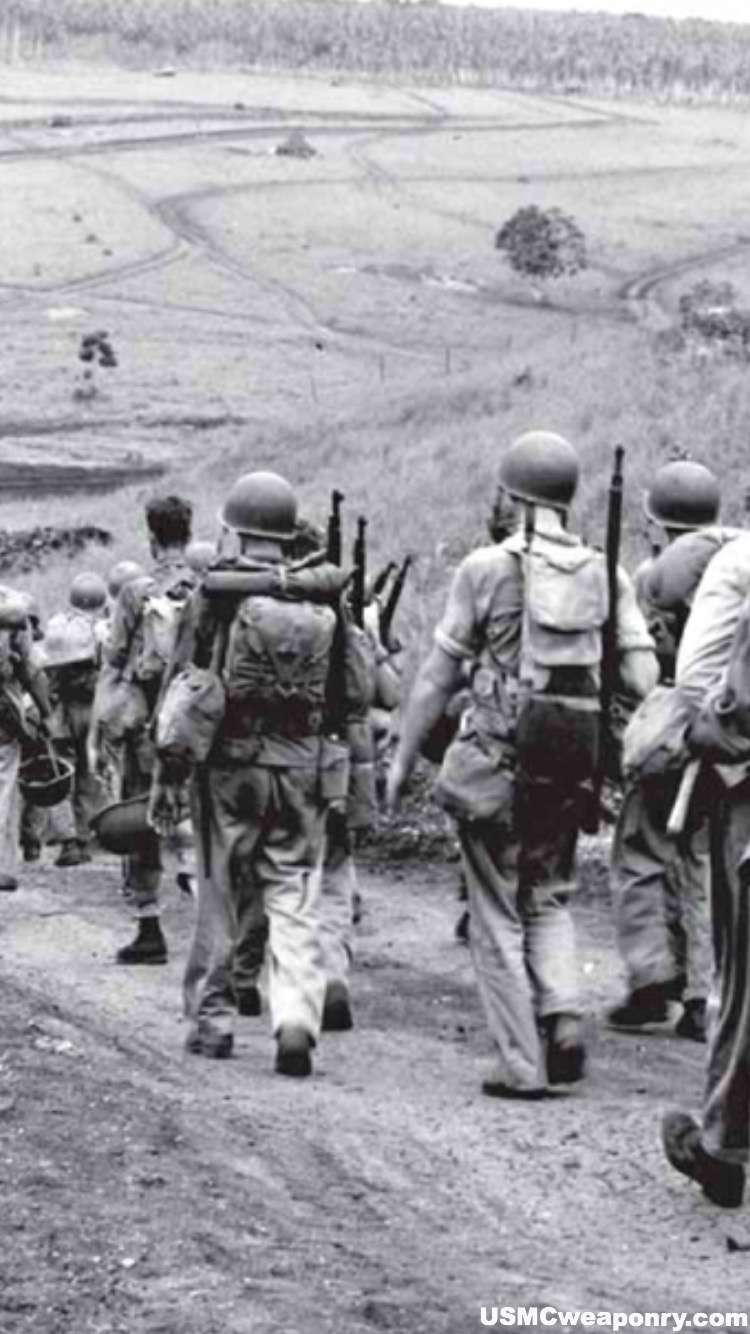

The end of a long run: as the 1st Marine Division left Guadalcanal in late 1942, the last regiments armed solely with the M1903 exited the battlefield. Their replacements, the men of the 2nd Marine Division, were partially armed with the new semi-automatic M1 Garand (NARA).

The month of November saw more elements of the 2nd Marine Division land as reinforcements on Guadalcanal. With them came the 2nd Raider Battalion, 8th Marine Regiment, and later in January the 6th Marine Regiment, all of which had a mix of M1 Garands and M1903s. This transition to the superior firepower of the M1 Garand would mark the end of the M1903 as the main rifle carried by the Marines into combat. The 2nd Marine Division, like all units in the Marine Corps were still very fond of their M1903s, but the advantage the M1 Garand provided in the close ranges and brutality that would come to typify the Pacific Theater was unmistakable. Though the Marine HQ had already ordered exchanging the M1903s of the Marine Divisions with M1s by mid 1942, the glowing reports of the M1s efficacy in combat were exactly the reaffirmation they had been hoping to hear.

Seen in the photos above, the men of the 2nd Marine Division carried a mix of M1 Garands and M1903s with them into the fray on Guadalcanal (photos: USMC/NARA).

As the 1st Marine Division ported for rest and refitting in Australia, the M1903s they carried with them would be quickly turned around for ships bound to the United States. Final overhauls would take place ad the Sand Francisco and Philadelphia Depots. With nearly 40% of the M1903s in the Marine Corps having served in combat in the South Pacific, many were sorely in need of rebuild. The result is what is easily the most well recognized and iconic version of the USMC M1903. These rifles have many previous Marine traits: Hatcher Holes, penetrate blued bolts (most with enlarged gas holes), stippled butt plates, and staked trigger guards, but are unique in their finish and sights. The finish is an unmistakable grayish-green color from the zinc phosphate parkerizing that was used during overhaul, and the numbered sights are seldom seen, instead utilizing generic #6 sights as the Marines had no intention of using these rifles for front line duty again. Barrels on WWII USMC rebuilds may be reused from previous contracts, but the majority are 1941-42 USMC contract Sedgley’s or 1942 Springfield Armory manufacture. Barrels typically have vice marks from installation, and the rear sights have been blued in a manner identical to the bolt. Sight covers are almost always absent, suggesting the Marine Corps did not bother installing them after overhaul on their way to storage. The quality of the overhaul is exceptional, and many of these rifles were either sold by the Marine Corps at PX facilities or the by the Civilian Marksmanship Program (CMP) decades later. The excellent craftsmanship has rendered these rifles fantastic shooters, and many can be seen on the line at vintage matches offered by the CMP today.

The WWII rebuild USMC M1903 is the most iconic and most encountered today. This particular rifle displays a wide range of WWII Marine rebuild traits (Griffin collection).

After the final overhauls, sizable amounts of USMC M1903s would be given to the Navy. Sailors would use the M1903 and updated M1903A3 in large quantities during WWII, and not be issued M1 Garands. Others would be given to local stateside units, as well as service organizations like the American Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) for use in ceremonies and funeral details. The trusted Springfield rifle had served the Corps faithfully, but a new world war saw it give way to a revolutionary weapon in the M1 Garand. The M1903 would continue to serve in limited roles throughout the end of the war, mainly as a grenade launching weapon, lightweight rifle for deep jungle patrols (most frequently employed by the Marine Raiders), or a scoped sniper rifle. In this capacity, it would serve admirably through the Korean conflict as well, often paired with a scoped sniper version of the M1 Garand. The range and accuracy of the M1903 Unertl sniper rifle would set the Marine Corps above peers and adversaries alike.

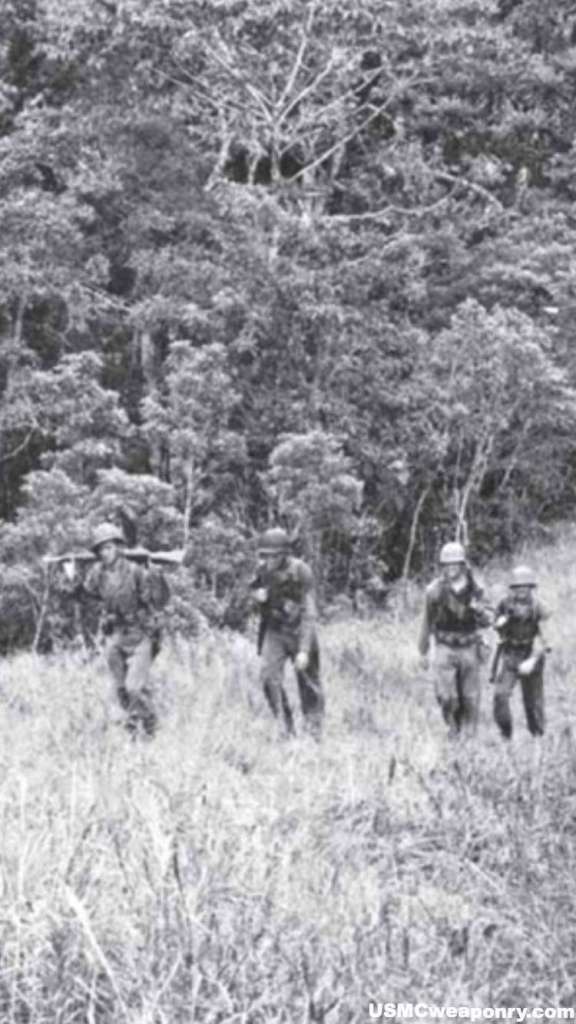

Marine Raiders on Bougainville in 1943, some still armed with the M1903, where it would serve as a grenade launching weapon or a lightweight rifle for long jungle patrols (USMC).

Top: M1903s in the hands of the 1st Marine Division on New Britain in late 1943. Bottom: a Marine with a C stocked M1903A1 on the pier at Tarawa (USMC & NARA)

PFC Edward J. Ross, a 1st Marine Division veteran of Guadalcanal who was awarded the Silver Star for actions in combat. Here he is pictured on Cape Gloucester still armed with his M1903 rifle (NARA)